Hospice Saint-Jean-de-Dieu

Name(s) of institution:

Hospice Saint-Jean-de-Dieu (a.k.a. Asile Saint-Jean-de-Dieu and Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu)

Hôpital Louis-Hyppolite Lafontaine (renamed 1976)

Institut en santé mentale de Montréal (renamed 2013

Opened:

1873

Location:

Longue-Pointe, Montréal, Quebec

Period of Deinstitutionalization:

1960-1980

Patient Demographic:

At its opening, the asylum was a huge complex with seventy-nine private rooms, twenty-seven rooms, two infirmaries, twenty-three dining rooms, fifty-one bedrooms, one hundred and fifty cells, and one kitchen with two floors and five pantries. In 1890, a fire destroyed a large part of the asylum and killed eighty-six people employees and patients—all women.

In 1898, the asylum population included 1,579 patients, 183 members of religious staff, 141 members of nonreligious staff, 3 doctors, and 2 chaplains. In 1922, there were 2,743 patients, 280 nuns (including 72 graduate nurses), 58 secular nurses, and 7 doctors. That same year, 270 patients died. In 1961, the hospital population peaked at 9,118 patients. In 1971, the social services houses accommodated 304 patients and the 43 affiliated houses accommodated 575 patients.

| YEAR | MALE | FEMALE | TOTAL | YEAR | TOTAL |

| 1875 | 156 | 252 | 408 | 1931 | 3639 |

| 1880 | 314 | 412 | 726 | 1941 | 6111 |

| 1885 | 453 | 498 | 951 | 1951 | 6159 |

| 1889 | 612 | 634 | 1246 | 1961 | 9118 |

| 1911 | 1971 | 1964 | 3000 | ||

| 1922 | 2743 | 1969 | 2652 |

Deinstitutionalization:

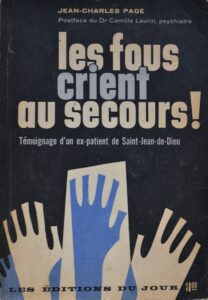

(Pagé, Les fous crient)

In 1961, Jean-Charles Pagé, a former patient of Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, published a book entitled Les fous crient au secours! (Insane people shout for help!) in which he denounced the conditions of confinement experienced by psychiatric patients and depicted Saint-Jean-de-Dieu Hospital as a prison. The book also suggested ways to improve patients’ quality of life of patients. The publication of the book and its success (4,000 copies were sold) elicited strong reactions that acted as the catalyst for the 1962 Bédard Commission and the government reforms that followed.

The Bédard Commission proposed extensive reform of the psychiatric system, restructuring it around psychiatric hospitals and general hospitals. It recommended modernizing the existing sixteen psychiatric hospitals in Quebec by limiting the number of in-patients and grouping quasi-autonomous services based on patient diagnosis. Hospitalization would be used only as a last resort, and hospitals would operate under an open-door philosophy, creating therapeutic frameworks whose ultimate goals were the patient’s recovery and reintegration into society. The asylum model would give way to hospitals offering the various scientific, material, and human resources required for this purpose. For their part, all general hospitals with more than 200 beds would be equipped with a Department of Psychiatry and an outpatient clinic to reach out to patients in their own environments.

Trans-institutionalization:

In 1964, Saint-Jean-de-Dieu set up a department to prevent unnecessary hospitalizations. It then added an evening service and a home care service. The hospital also deployed teams of multidisciplinary care workers that incorporated new professionals (social workers, psychologists, occupational therapists, etc.) and provided community services with the intention of providing a link between the hospital and the family.

Outside residences accommodating at least five residents each were also established. These homes, which numbered forty-six in 1964, were designed to replace the hospital with a friendlier, more homelike environment. In 1972, these residences accommodated 304 people, of which about a third were definitively discharged from the hospital.

In 1969, the hospital established a new system, the “Service de psychologie communautaire de l’Est” (Eastern Community Psychiatry Service), which aimed to avoid patient hospitalization and to meet the demand for care within families and communities by providing home care.

Work Therapy into Occupational Therapy:

Before de-institutionalization, patients hospitalized in Saint-Jean-de-Dieu were expected to perform labour whenever their conditions permitted. In Les fous crient au secours!, Jean-Charles Pagé reported that most patients worked to maintain the various facilities of the hospital complex. “The Centre consists of various workshops for repairs in all rooms. Each trade is represented. Depending on requirements, there will be shoemakers, machinists, painters, carpenters, plasterers. Patients assigned to these structures must be as punctual as if they worked for a company. Their day on average is six to seven hours … Their wages amounted to seventy-five cents per week, and as a bonus, a small pack of cigarettes.”

The Bédard Commission called for manual labour to be replaced with activities of a therapeutic nature. In 1964, the farm buildings at Saint-Jean-de-Dieu were demolished, signalling an end to agricultural work therapy at the institution.

Patient into Person:

In the mid-1960s, several affiliated homes introduced new rehabilitation therapies: art therapy, music therapy, body language, and social expression. At the hospital, a first series of “remotivation” classes was given. A separate library for patients and two audiovisual centres were also created.

Rayons d’espoir (Rays of Hope), a newspaper produced by patients of Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, was published. In 1972, more than 1,500 copies were printed.

Architectural changes were also made to the hospital complex. In 1964, bars and grilles were replaced by locked windows.

Staffing in the Deinstitutionalization Era:

After the Bédard Report of 1962, the provincial patient stipend was increased, allowing the hospital to hire more qualified staff.

In 1964, the hospital obtained accreditation for training interns from the University of Montréal and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. By 1969, in addition to having graduate psychology students on-site, the hospital signed several service contracts with colleges to allow nursing students to intern at the hospital. Agreements were also established with some general hospitals.

In 1973, the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu Hospital signed an affiliation agreement with the University of Montréal and officially became a university teaching hospital.

In the 1970s, deinstitutionalization and an increasingly secular staff component at Saint-Jean-de-Dieu led to the departure of the Sisters of Providence, who had run the hospital over the previous century. Dr. Denis Lazure, who was designated General Director in 1974, reorganized the hospital according to the principle of specialization. In 1976, the hospital was renamed Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine Hospital and was organized around three areas: a short-term hospital centre, a centre for extended care (longer than three months), and a hospital centre to care for incurable patients. This structural reorganization caused a wave of resignations among staff, and the number of psychiatrists subsequently fell from forty-eight to twenty-one.

Sources:

Bédard, Dominique, et al. Rapport de la Commission d’études des hôpitaux psychiatriques. Quebec City: Ministère de la santé de la province de Québec, 1962.

Boudreau, Françoise. De l’asile à la santé mentale : les soins psychiatriques : histoire et institutions. 2e édition. Montréal: Saint-Martin Publishers, [1984] 2003.

Fleury, Marie-Josée, et Guy Grenier. “Historique et enjeux du système de santé mentale québécois.” Ruptures, revue transdisciplinaire en santé vol. 10, n° 1 (2004): 21–38.

Keating, Peter. La science du mal: L’institution de la psychiatrie au Québec, 1800–1914. Montréal: Boréal, 1993.

Lecomte, Yves. “De la dynamique des politiques de désinstitutionnalisation au Québec.” Santé mentale au Québec vol. 22, n° 2 (1997): 7–24.

L’Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Québec (IUSMQ). “La mémoire des édifices: des noms gravés dans la pierre.” L’Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Québec (IUSMQ). https://www.iusmm.ca/institut/professionnels-et-publications/chroniques-historiques/noms-graves-pierre.html.

Pagé, Jean-Charles. Les Fous crient au secours! Montréal: Éditions du Jour, 1961.

Sœurs de la Providence. Un héritage de courage et d’amour ou La petite histoire de l’Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu à Longue Pointe, 1873–1973. Montréal: Communauté des Soeurs de la Providence, 1975.

Wallot, Hubert. La danse du fou entre la compassion et l’oubli : Survol de l’histoire organisationnelle de la prise en charge de la folie au Québec depuis les origines jusqu’à nos jours. Beauport: Beauport Publications MNH, 1998.