The Asylum Project in Western Canada

By Arthur Allen

I call it the Asylum Project, the construction and operation of buildings for the shelter and treatment of mentally ill people in Europe and North America. It took place from approximately 1800 to 1960. The Asylum Project began with high hopes and promises and ended with empty buildings, and people back on the street, or in the bush in Western Canada. It started out with architectural optimism, but practitioners, critics, educators, and historians of architecture have been silent about its sad conclusion. We should not leave that void unfulfilled.

The asylum was intended as a safe place for the treatment of the mentally ill. During its best days, the practice of Moral Management provided hospital occupants with social activities and opportunities for meaningful work. In Western Europe and North America, the Project quickly erected many large buildings that it should be recognized as a significant event in the history of architecture. The establishment of asylum grounds and adjoining farms added to the visual and logistical scope of the asylum. Yet early optimism and enthusiasm gave way to the functional failure of large and overcrowded public institutions that displaced the era of moral management.

Architects were part of this problem because they were contracted to design buildings for storage, not treatment, and continued to plan large hospitals in spite of widespread complaints that the massive and crowded buildings were unmanageable. Experience in design of mental hospitals and long-term interest in the subject leads me to believe that architects have been silent not only because mental illness is a difficult subject, but because the story of asylum buildings challenges the complex web of professional, artistic, and business interests that exist in architecture. The ethics and morality of activities that take place within buildings should be of concern to architects, and the eagerness of architects to build dysfunctional psychiatric warehouses needs to be recorded and taught in classes on professional ethics.

My exhibit sets out the architecture of eight asylums built in Western Canada between the years 1878 and 1923. They are presented in chronological order of their construction. Employment payrolls and supply of goods and services to a mental hospital made asylums unusually attractive prospects for new towns in the west. Communities competed as potential sites, and political connections were always possible. Asylums were busy, organized places, usually located a short distance from town limits of the time. At that, they had important connections to their communities in spite of physical and mental separation.

For each institution, I set out the stories of sites, buildings, grounds and patient life as a collection of material useful to historians, architects, and general readers. I persist with attention to routine information about, and use of, these architectural spaces and the areas that surrounded them. Why? Because these details had an immediate effect on the life, safety, and mental health of patients, and because we will be wise to remember the impacts of the Asylum Project on the people it was intended to assist.

On the Reading of Plans

Architectural publications invariably illustrate buildings with no people shown in photos or on plans. I reverse this practice, and in this way ask readers to pay attention first to the occupants, then to the building. While not exciting, floor plans of buildings open views into the minds of architects and their clients. On close examination, they tell how the patients are intended be classified, organized, placed, and given or denied the opportunity to move about. A note “side-room” on a ward plan indicates forcible isolation of a patient. “Courtyards” and, “gardens” printed on a plan tell of fresh air and sunshine, and some freedom of movement. The word “dormitory” tells of large interior space, its rows of beds denying patients’ privacy. Rigorous axial symmetry and long views from central points in the geometry of a plan indicate operations based on surveillance and control of patients at all times.

Three Asylum Observers

Dr. T.J.W. Burgess, MB, President of the Geological and Biological Sciences Section of the Royal Society of Canada, and first superintendent of the 1880 Protestant Hospital for the Insane, in Verdun, Quebec. References to Burgess in this exhibit refer to his presidential address of 25thMay 1898, titled, “A Historical Sketch of our Canadian Institutions for the Insane.”

Dr. Henry M. Hurd, MD, LLB, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University. Hurd was editor of a four-volume book, published in 1917, recording observation and evaluation of mental hospitals throughout North America. The book was titled, The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada, and included T.J.W. Burgess among its contributors, reporting on Canadian institutions.

Dr. Clarence M. Hincks, MD, of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene. From 1918 to 1950, the CNCMH surveyed and reported on mental health issues at the request of the government of each province across Canada. Reports written by Hincks were extensive and considering a wide range of mental health issues. References herein to Hincks refer to his surveys.

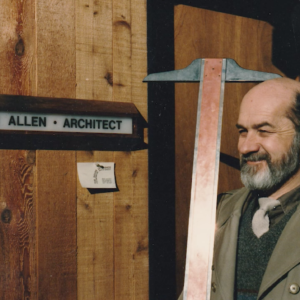

About the Exhibitor

Arthur Allen was born in Lacombe, Alberta in 1932 and trained as an engineer at the University of Alberta before graduating from the University of British Columbia in 1957 with a Bachelor of Architecture. Arthur’s architectural career was spent in different parts of western Canada. He worked as an institutional architect in the 1950s and 1960s on the Weyburn Mental Hospital and the innovative Yorkton Psychiatric Centre, designing and overseeing renovations. He was a consultant to Saskatchewan public health programs in the early 1970s. From 1975, Arthur was based out of Vancouver, BC, taking on projects for the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia, Trinity Western University, and other civic and private corporations.

Arthur was also a writer, lecturer, and craftsman. These first two talents came together with a passionate critique of unfeeling institutional architecture that limits and confines rather than supports and heals. He believed that architects have an ethical responsibility to design buildings that are healthy places for the people who live and work in them. This exhibit, and the sample of Arthur’s writings and lecture notes that are posted below, are an urgent invitation to consider mental health architecture from a people perspective and to create caring environments for those in mental distress.

The sketches in this exhibit were all created by Arthur, some based on historical photographs.

We thank Arthur’s family for their help in creating this exhibit.