Riverview

Name(s) of Institution:

Hospital for the Mind at Mount Coquitlam (1913)

Essondale Hospital (renamed 1913)

Riverview Hospital (renamed 1965)

Opened:

April 1, 1913

Location:

Coquitlam, British Columbia

Period of Deinstitutionalization:

1955–1975

Patient Demographic:

| YEAR | ESSONDALE/RIVERVIEW | CREASE CLINIC |

| 1954 | 3,484 | 215 |

| 1955 | 3,419 | 267 |

| 1959 | 3,279 | 241 |

| 1963 | 2,740 | 229 |

| 1965 | 2,689 (257)* | 229 |

| 1968 | 2,683** |

* In 1965, boarding home placement began. Numbers in parentheses reflect boarding homes.

** For 1968, Essondale/Riverview includes the numbers for the Crease Clinic.

Deinstitutionalization:

Acknowledging that there would be a continued need for long-stay beds in hospitals like Essondale, the 1950 annual report of the new amalgamated BC Provincial Mental Health Services noted that future policy should be directed at “increased early active treatment to prevent patients entering into the long-term treatment mental hospital area” and at “alleviating present overcrowding” in existing facilities. F. G. Tucker, who began as a resident physician at Essondale in 1953, became director of the Crease Clinic in 1959 and then took the post of Deputy Director of Mental Health Services four years later. Tucker was a key figure in the move toward de-institutionalization.

The 1951 establishment of the Crease Clinic (considered state of the art when it opened) on Essondale grounds was part of a push toward short-stay outpatient care with a focus on recovery and rehabilitation within a few months of hospitalization. New psychiatric medications chlorpromazine and largactil were introduced for patient use at Essondale in 1954.

A co-operative relationship between the Psychiatric Department at the new University of British Columbia (UBC) medical school further helped bolster the idea that the new clinic was part of a larger provincial program of scientific advancement, research, and professional training. By the mid-1960s, senior UBC undergraduate students in psychology were visiting Essondale as part of their class work.

A new provincial Mental Health Act was passed in 1964 and came into force April 1, 1965, amalgamating the Crease Clinic and Essonale Provincial Hospital under the new name Riverview Hospital and combining five older laws that dealt with mental health. Designed to accommodate a number of new policy agendas, the new act allowed for for short-stay, voluntary treatment and fostered the development of locally based mental health services.

Created by the provincial government in 1972, the new Riverview Hospital Advisory Board immediately formed a committee to develop plans for closing the hospital within five years. Dr. Richard G. Foulkes’ 1973 report, Health Security for British Columbians, included a scathing assessment of Riverview and a call for its immediate closure. This did not happen, but the facility introduced a Home Treatment Project during this period and expanded the movement of patients through institutional rehabilitation programs and into community boarding homes.

In 1979, pushed by increased consumer/user involvement, and with the patient population at Riverview reduced to 1,100, the province began the process of re-evaluating the efficacy of institutional care. The Mental Health Planning Survey of that year revealed problems with centralization, patient transfers, and accounting procedures. By the mid-1980s, plans were underway to further downsize Riverview, and a renewed and expanded ideal of rehabilitation shaped the policy agenda in the 1987 New Mental Health Consultation Report: A Draft Plan to Replace Riverview Hospital.

In 1986, a new Family Centre opened in the Tuck Shop building, meant to involve families in the Riverview community and foster greater understanding of mental health issues. The early 1990s saw the establishment of a Bridging Program to link patients with people and community services and the use of cottages on the hospital grounds as semi-independent housing for patients transitioning from institution to community. In 1996, the Psycho-Social Rehabilitation Program was created to encourage patient and family involvement in treatment plans and foster life skills for successful community living.

Over the past twenty-plus years, Riverview has served as a popular filming location for television and film productions, including The X-Files, Battlestar Galactica, Elf, and Smallville, and also, reportedly, as a grow-op. Through the 1980s and successive decades, key buildings on the Riverview site were closed: West Lawn in 1983; Crease Clinic in 1992; East Lawn in 2005; North Lawn in 2007. Riverview closed officially in July 2012, but controversy regarding its closure continues. Three small recently opened buildings operated by Fraser Health remain in use on the Riverview site: Connolly Lodge (2001), Cottonwood Lodge (2006), and Cypress (2008.)

An institutional feature of the deinstitutionalization period at Essondale was an increased specialization in mental health treatment on the Coquitlam site. In 1959, a new 328-bed Valleyview facility for geriatric mental health patients was opened as the research and treatment wing of a provincial system. Smaller “branch plant” institutions were established at Terrace (Skeenaview) in northern BC and in the Okanagan community of Vernon (Dellview) .

In 1965, the Riverside building at Colony Farm was converted into a maximum-security facility with a section set aside for the treatment of chronic alcoholics. In the mid-1970s, the Forensic Psychiatric Service Commission was established on the Riverside site. In 1974, the Organic Brain Syndrome Project (later the Neuropsychiatry Program) was established to treat patients with brain injuries, making use of space at the Crease Clinic, and the North and Centre Lawn buildings.

Transinstitutionalization:

Essondale was part of an early deinstitutionization experiment for female patients. The New Vista Home for Women [link to NV exhibit], established in the early 1940s by Ernest Winch, a long-time Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) member of the BC Legislature, offered accommodation and support to dozens of female ex-inmates. The provincial government took over the facility in 1947. Charitable organizations for men transitioning to community care during the 1950s included short-term accommodation at the YMCA and the Salvation Army hostel before employment placement. In 1965, the government established a fledgling boarding home program, aiming to expand this service across the province and “clear more beds of patients in provincially operated institutions and return them to their community.”

Alder Lodge opened in Coquitlam in 1969, a pre-community placement facility for fifty male patients replacing the YMCA and the Salvation Army hostel and operating on a bigger and more organized scale. The Lodge began relocating patients to group homes and community placements in 1970. In the 1970s, Vista, along with Venture, a ten-bed emergency residence for men, was part of the Greater Vancouver Mental Health Service (GVMHS). By 1974, the boarding home program was accommodating 1,700 people in 280 facilities, a figure that included individuals with learning disabilities.

Another early trans-institutional initiative in the western city was the 1915 establishment of a psychiatric ward at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH). The VGH 1945 annual report stated that old Ward X, a former tuberculosis ward, was the site of a modern psychiatric ward. Buttressed by post-war federal cost-sharing arrangements, BC moved to establish psychiatric wards in general hospitals. When the University of British Columbia Hospital opened in 1968, it included a psychiatric unit in the Detwiller Pavilion.

The first community mental health centre in the province opened in Burnaby in 1957. The Mental Health Centre (Burnaby) offered early outpatient treatment with the goal of “preventing their admission to a mental hospital,” a social club run by Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) volunteers, and aftercare for patients who had been hospitalized. Community mental health teams were part of John Cumming’s comprehensive 1972 “Vancouver Plan,” which offered community-based services for people with serious mental health difficulties. By 1974, there were nine multidisciplinary GVMHS teams across Vancouver and Richmond working in facilities close to public transit routes and offering drop-in services, free coffee, and opportunities for building basic life skills. In a somewhat unorthodox practice, GVMHS teams worked with community groups like Coast Foundation and the radical Mental Patients Association (MPA) to offer after-hours emergency services and a suicide prevention program. By the mid-1970s, there were thirty mental health clinics operating in different regions of the province, providing outpatient services, and emphasizing preventative mental health.

MPA was formed in Vancouver in 1971 as a utopian grassroots response to deinstitutionalization and the tragic gaps in community mental health services. Expanding rapidly, it soon offered co-op housing, employment, and a vibrant drop-in centre. Over the 1970s, Vancouver’s Coast Foundation expanded into the housing field, managing several apartment buildings and “three-quarter” houses with a daytime coordinator and a communal kitchen. Both Coastal and MPA were able to enter the housing market and expand their housing offerings in the inflationary real estate market of the late 1970s because of interest-free loans available through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Influenced by the MPA model and emerging notions of community living, New Westminster’s Pioneer Lodge was opened in 1980, spearheaded by a partnership of Riverview patients, volunteers, and nurses.

Work Therapy into Occupational Therapy:

Patient work was always an essential part of Riverview’s institutional economy; indeed, patients had worked to clear the original site in 1908 and 1909. Visiting in 1918, C. K. Clarke of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene commented, “The entire history of this institution, brief as it is, presents a continuous story of the uses to which patient labour can legitimately be turned.” The fiscal possibilities of patient labour found a convenient echo in the medical belief that work itself constituted the best kind of therapy, hence the term “work therapy.” Female patients did cleaning, canning, laundry, gardening, and sewing. Male patients worked on wards, in the garden, on the grounds, and they managed the fields and chores of the thriving Colony Farm, recognized in the 1920s as one of the top farming operations in Western Canada. Colony Farm remained in operation until 1983.

Replacing the unpaid work encompassed by “work therapy,” occupational therapy began to play a role in patient rehabilitation. Annual Reports from the early 1950s recount the successes and failures of the job placement program in the men’s division of Essondale’s Rehabilitation Department, regarded as a pilot project in the field. By 1950, an average of 106 patients were attending occupational therapy shops at Riverview each day, undertaking such activities as needle, wood, metal, and leather work, as well as weaving, painting, and pottery. The Industrial Therapy Building at Essondale was constructed in 1963 at a cost of $505,000, with the goal of training patients so that they could resume life in the community as waged workers. Male patients were assigned to courses in cabinetry, upholstery, furniture finishing, metalwork, printing, electronics, tailoring, and shoemaking. By 1987, Riverview patients participating in vocational skills training programs were given an “incentive allowance” starting at $15 per week and increasing over time to $180 per month.

Patient into Person:

Essondale’s newsletter, The Leader, began publication in 1947 and ran for the next thirty years in various formats. Like similar institutional publications across Canada, The Leader kept patients, staff, and families informed about institutional activities and news, and served as an outlet for patient self-expression through poems, drawings, and writing.

Established in 1951, the Crease Clinic functioned under a separate legal system for its admissions, meant to allow patients to enter the facility on a voluntary basis and terminate treatment at any time. The idea behind this policy was to destigmatize mental health issues by presenting them as similar to physical illnesses and thus encouraging people to seek help in the early stages of a mental health crisis. By the 1950s, Essondale patients might participate in an array of recreational options available to Canadians not residing in a mental health institution: tennis, bowling, weekly dances, swimming, the theatre, board games, bingo, and an annual sports day. Many of these activities were centred around Pennington Hall, which opened in 1950, an unassuming building on the Essondale site that housed a gymnasium, café, theatre, and bowling alley, and remained the social hub of Riverview throughout the deinstitutionalization period.

A 1973 experiment with “pub therapy” using actual alcoholic beverages took place with the establishment of the weekly western-style Longhorn Saloon on Ward F1 in the East Lawn (male building). Integrating male and female patients, the saloon was intended to engage withdrawn patients in social activity and to bring elements of ordinary community living into the institution.

As deinstitutionalization gained momentum, there was an accompanying increased emphasis on turning patients into “responsible citizens.” From the early 1960s, rehabilitation programs at Essondale emphasized basic open wards and ward community meetings to give greater freedom and to embody the notion of democratic participation.

In 1977, a Mental Health Law Program was established to provide legal advice and representation to people who had been involuntarily detained under the BC Mental Health Act, setting in place review panels consisting of a chair, a doctor, and a patient representative. This was both a real and symbolic marker of patient rights at Riverview. A decade later, patients residing in psychiatric facilities obtained the right to vote in federal elections. During 1993 and 1994, the BC Office of the Ombudsperson undertook an extensive investigation into patient, family, and community concerns about Riverview. Following the publication of the resulting report, Listening: A Review of Riverview Hospital, the institutional community established a Patient Sexuality Policy and a Charter of Patient Rights, both Canadian innovations for psychiatric hospitals.

Staffing in the Deinstitutionalization Era:

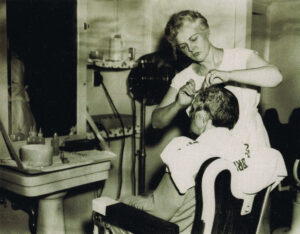

The use of Essondale as a training facility for nurses reached its height in the 1950s, the same time the patient population peaked. In 1953, more than 200 nurses graduated from Essondale’s Nursing School, which offered classroom learning alongside practical experience on patient wards. But the pattern over the deinstitutionalization period was to phase out nursing education at the facility. In 1973, Riverview’s nursing program was transferred to the British Columbia Institute of Technology and the last class of psychiatric nurses graduated from Riverview. The loss of nurses-in-training was immediately felt on patient wards.

The type of mental health practitioners required by Riverview broadened with the advent of community mental health. Increasingly, a team of nurses and occupational and recreational therapists were regarded as necessary to reduce hospital stays and facilitate patients’ transition back into the community. In the annual provincial mental health service reports of the late 1950s, the occupational therapist (gendered female) was understood as being responsible for fostering sociability, motivation, concentration, and productivity among patients, but nurses were also meant to be actively engaged in this work. Riverview staff were discouraged from wearing uniforms in order to break down barriers between patients and their caregivers.

In March 1959, Essondale members of the BC Government Employees Association went on strike for four hours over the issue of bargaining rights. Nurses blocked other practitioners from reaching the Riverview site, declaring that the patients would be fine without them, but the nurses were immediately ordered back to work by the BC Supreme Court. A decade later, the Association became the BC Government Employees Union.

All BC mental health facilities, including Riverview, experienced staff shortages throughout the late 1960s and 1970s. In January 1968, forty beds at Riverview had to be closed because there were not enough qualified psychiatrists to care for patients. In 1974, staff turnover across the province in mental health was 30 percent, a total of thirteen Riverview psychiatrists had resigned, and efforts were underway to recruit nurses from the United Kingdom.

Sources:

BC Mental Health Services. Annual Reports, 1950–1968.

Beamish, Dave. Oral history interview, Vancouver, June 23, 2010.

Beckman, Lanny. “Us and Them.” History in Practice: Community-Informed Mental Health Curriculum. 2014. [link to site]

Beckman, Lanny, and Megan J. Davies. “Democracy is a Very Radical Idea.” In Mad Matters, edited by Brenda LeFrancois, Robert Menzies, and Geoffrey Reaume, 49–63. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press, 2013.

Boschma, Geertje. “Deinstitutionalization Reconsidered: Geographic and Demographic Changes in Mental Health Care in British Columbia and Alberta, 1950–1980.” Histoire Sociale/Social History 44, no. 88 (2011): 223–256.

Choi, Rosalyn, and Geertje Boschma. “The Emergence of Survivor Groups in BC: A Historical Perspective.” Vancouver Acute & Community Mental Health Services Newsletter 1, no. 7 (2011): 3–4.

Davies, Megan J. Into the House of Old: A History of Residential Care in British Columbia. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Davies, Megan J. “The Patients’ World: British Columbia’s Mental Health Facilities, 1910–1935.” MA Thesis, University of Waterloo, 1989. [link to MA thesis]

Faviell, Mark. “Essondale at Port Coquitlam 1961.” Photograph. 2011. Available from Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/26005095@N02/5595122881/in/photolist-9wqt6T-9uWegQ-9uH7Xr-9uGZoT-9uTgJp-9wuo5y-9x6L4Z-9x6J2t-9uWxpW-9uGN3M-9Cpjie (accessed August 15, 2013).

Filkow, Sid. Oral history interview. June 28, 2010. Saltspring Island, BC.

Gutray, Bev, and Marina Morrow. “Reopening of Riverview Hospital Not the Answer.” Vancouver Sun, September 27, 2013. https://www.vancouversun.com/business/Reopening+Riverview+Hospital+answer/8964824/story.html

Marijuana.com. https://www.marijuana.com, accessed June 20, 2014.

Menzies, Robert. “Ernest Winch and the Women of New Vista.” After the Asylum. 2014.

Speirs, Karen. Riverview Hospital: A Legacy of Care & Compassion. British Columbia Mental Health and Addiction Services, 2009.