Community Living

In 1976, at the age of 49, having lived in institutions for 42 years, Doreen was released into the Alberta prairie town of Red Deer, whose population was then just over 30,000. At first she lived semi-independently in a group home with the help of social services, including through regular contact with a social worker, and a variety of public supports. Three months later, Doreen stuck out on her own for the first time in her life, renting a one-bedroom basement apartment, supported through a combination of provincial and federal programs for adults with disabilities. She commemorated this moment in her diary with a tiny cutting of the classified ad that described her new accommodations: “1 bedroom suite, refrigerator, stove, includes heat, $290/month.”

In 1976, at the age of 49, having lived in institutions for 42 years, Doreen was released into the Alberta prairie town of Red Deer, whose population was then just over 30,000. At first she lived semi-independently in a group home with the help of social services, including through regular contact with a social worker, and a variety of public supports. Three months later, Doreen stuck out on her own for the first time in her life, renting a one-bedroom basement apartment, supported through a combination of provincial and federal programs for adults with disabilities. She commemorated this moment in her diary with a tiny cutting of the classified ad that described her new accommodations: “1 bedroom suite, refrigerator, stove, includes heat, $290/month.”

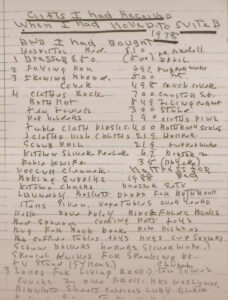

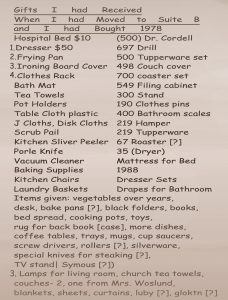

Her move triggered a dramatic set of changes in Doreen’s life, not the least of which included living on her own, p aying her own bills, becoming an active member in her church, securing appropriate employment, maintaining her social services appointments, cooking, cleaning and assuming a host of responsibilities. She was familiar with some of these activities, having participated in cooking and cleaning at the provincial institutions as a trainee. Managing money, however, had only ever been an exercise within the protective walls of the institution, whereas taking public transit, making appointments with social workers, doctors, psychiatrists, and others had never been part of the closely monitored functions of the institution. On the outside, life was very different and people like Doreen who had spent their entire lives within a carefully structured and supervised environment carried many of their institutionalized habits into the community. This may be why when Doreen set up her own apartment, she meticulously recorded a list of her entire set of belongings, including notes as to whom had given each item or where she had purchased them and at what cost. She also kept a page of signatures from all the people who visited her home, including social workers, friends, home care nurses and Canadian Mental Health Association representatives.

aying her own bills, becoming an active member in her church, securing appropriate employment, maintaining her social services appointments, cooking, cleaning and assuming a host of responsibilities. She was familiar with some of these activities, having participated in cooking and cleaning at the provincial institutions as a trainee. Managing money, however, had only ever been an exercise within the protective walls of the institution, whereas taking public transit, making appointments with social workers, doctors, psychiatrists, and others had never been part of the closely monitored functions of the institution. On the outside, life was very different and people like Doreen who had spent their entire lives within a carefully structured and supervised environment carried many of their institutionalized habits into the community. This may be why when Doreen set up her own apartment, she meticulously recorded a list of her entire set of belongings, including notes as to whom had given each item or where she had purchased them and at what cost. She also kept a page of signatures from all the people who visited her home, including social workers, friends, home care nurses and Canadian Mental Health Association representatives.

Institutional labels, surveillance and social criticism followed people out of the provincial facilities into the community of Red Deer, creating a new set of problems. Former patients now faced a host of practical and psychological obstacles. Those who may have exhibited characteristics of an institutionalized existence, for example requiring extra time at the grocery till, or needing help figuring out a bus schedule, were not necessarily easily absorbed into the community.

Outside of the walls of the hospital Doreen became an active member of her community, providing child care supports for local mothers, and helping her fellow deinstitutionalized friends and acquaintances as they negotiated the contours of out-patient care, social services, bus routes, bill payments and the rhythms of an independent life. On her own, perhaps more successful than others, Doreen embraced a new phase of life: one marked by social activism and disability advocacy. Generating strength from her religious convictions, Doreen spent the next twelve years writing letters to editors, dignitaries, and even the Queen, promoting the rights of individuals with disabilities as well as working closely with deinstitutionalized people to help them realize their capabilities. She stated “when I speak, I hope to change people’s attitudes toward the handicapped from believing in their own abilities. Handicapped people are like everyone else.” Doreen became involved with a variety of organizations, including Alberta Association for the Mentally Retarded, the Epilepsy Association, the Brain Injury Society, the Hearing Impaired Society, and People First. A closer look at her more intimate and immediate responses shows that her activism was not inevitable but rather evolved out of her experiences in the community. In 1988 the town of Red Deer officially recognized Doreen’s humanitarian efforts and presented her with the Air Canada Heart of Gold Award.