Citizens’ Mental Health

In 2010 Megan Davies spoke with retired psychiatrist Hugh Parfitt, a pioneer Vancouver community mental health professional, about what it was like to be on the ground in the early 1970s building the Kitsilano Mental Health Team with a radical mental health organization like MPA just down the road. Parfitt described the team’s early interaction with MPA as a two-way learning process that took place over time.

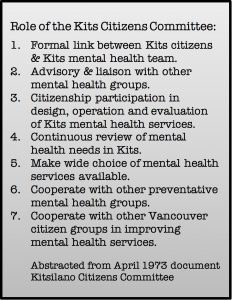

Hugh Parfitt stressed that the new team, enacting a new governmental plan and operating from a professional perspective, had sought innovative ways of democratizing mental health work and bringing community organizations like MPA on board. He really wanted to bring that point across. Hugh talked specifically and at some length about the Kitsilano Citizens’ Committee, a short-lived initiative of the new team.

Citizens committees were held as the model in the new Greater Vancouver Mental Health Project (GVMHP), addressing psychiatrist John Cumming’s emphasis on bringing local communities on board that he detailed in a section of his 1972 “Vancouver Plan.” Commissioned under the Social Credit government, but implemented by NDP Minister of Health Dennis Cocke, Hugh told us that Cumming’s blueprint for community mental health in the western city purposefully established the service as a separate society to allow it to operate independently of the more staid provincial mental health bureaucracy.

The Kitsilano Citizens’ Committee appears to have been the most active of the Vancouver committees and was likely the most critical of the mainstream mental health system. The MPA had a strong representation on the Committee’s meetings and reported regularly on its progress and decisions in In a Nutshell. In late January 1973 Hugh began the process of establishing a community mental health team in Kitsilano, speaking first with individuals in the community, and then hosting an invited meeting in March with representatives from the local health unit, the school board, and local service organizations including MPA. Subsequent meetings were held throughout the spring, culminating in a public meeting in mid-May. Hugh was disconcerted at first when a resolution was presented to freeze all project development for a mental health team in Kitsilano until a citizens’ advisory committee was “formed and functioning” but, reflecting that this indicated that the citizenry wanted to have a say, he voted in favour.

The Kitsilano Citizens’ Committee appears to have been the most active of the Vancouver committees and was likely the most critical of the mainstream mental health system. The MPA had a strong representation on the Committee’s meetings and reported regularly on its progress and decisions in In a Nutshell. In late January 1973 Hugh began the process of establishing a community mental health team in Kitsilano, speaking first with individuals in the community, and then hosting an invited meeting in March with representatives from the local health unit, the school board, and local service organizations including MPA. Subsequent meetings were held throughout the spring, culminating in a public meeting in mid-May. Hugh was disconcerted at first when a resolution was presented to freeze all project development for a mental health team in Kitsilano until a citizens’ advisory committee was “formed and functioning” but, reflecting that this indicated that the citizenry wanted to have a say, he voted in favour.

Lanny Beckman was among the community participants who volunteered on the steering committee entrusted with the task of drafting a proposal for the Kitsilano mental health project. “We were very wary of whether or not this was designed to undermine organizations like MPA, and sort of normalize them and then control them,” his friend and housemate Stan Persky said, recalling the group’s first responses to the notion of a citizen’s committee. Barry Coull raised concerns on the pages of the Nutshell about the creation of a little Riverview in the neighbourhood. But Lanny’s inked jottings on his 1973 copy of Cumming’s Vancouver Plan suggest a pragmatic willingness to engage in the process: “Patronizing, but we can agree in principle,” and “OK, let’s take him up on it!”

Lanny was willing to take a seat at the table, and went on to participate in the volunteer work of the committee along with Persky, Barry Coull, Fran Phillips, Jackie Hooper and other MPA members. His collection of papers saved from the period overlap with those shared by Hugh Parfitt, and their scrawled notations on these documents make us privy to a kind of historical conversation. At the May 22nd meeting it was agreed that those present would constitute the Citizen’s Committee. Over the next five months the Kitsilano Citizens’ Committee worked to plan the future shape of community mental health in their neighbourhood. The committee functioned through an elected 5-person steering committee to do the administrative work of preparing meeting agendas and documents, making phone calls, writing letters, acting as liaison with the GVMHP, and chairing meetings. Hugh served with Barry Coull on the steering committee. Lanny was elected to the 3-person personnel committee responsible for looking at hiring and preparing budgets. The aim of the group was to have a “significant percentage of its members as nonprofessional citizens interested in mental health.”

As illustrated by Hugh Parfitt’s experiences, when employees of the new Metropolitan mental health services engaged with citizens in the neighbourhood they frequently found themselves in agreement with the community members. Their political stance often aligned closely with that of the community, and hence MPA. In his 2010 interview Hugh seemed to further nuance this same point; in 1973 community input seemed essential to the success and effectiveness of the new mental health team in Kitsilano.

In a Nutshell’s reports of the community meetings demonstrate the organization’s engagement with the tantalising notion of “unprecedented community control of a government project.” MPA members attending the community meetings shared their views imbued with a fierce anti-psychiatric critique, yet also demonstrated a willingness to make community services work in alignment with MPA ideals of self-help, self-organization and participatory democracy.

Hugh and his colleagues invested time to let the steering committee, elected on behalf of the community, prepare policy guidelines for the proposed community mental health team and the personnel committee prepare an alternative budget. The Kitsilano Citizens Committee wanted to hire two non-professional mental health workers and a nurse with community and psychiatric experience, and allocate funds for patient travel, a crisis centre, a drop-in, and emergency food and clothing. Diverse views had to be brought together and not all community members involved were interested in more mental health services in the neighbourhood. Yet, “we did come to a final proposal after quite a few months of negotiations,” Hugh recalled.

Hugh and his colleagues invested time to let the steering committee, elected on behalf of the community, prepare policy guidelines for the proposed community mental health team and the personnel committee prepare an alternative budget. The Kitsilano Citizens Committee wanted to hire two non-professional mental health workers and a nurse with community and psychiatric experience, and allocate funds for patient travel, a crisis centre, a drop-in, and emergency food and clothing. Diverse views had to be brought together and not all community members involved were interested in more mental health services in the neighbourhood. Yet, “we did come to a final proposal after quite a few months of negotiations,” Hugh recalled.

The plot of Hugh’s story was revealed towards the end of his 2010 interview, when he explained that the final draft of the Kitsilano Citizens’ Committee’s proposed budget was dismissed by higher levels of government. “Months wasted – citizens’ participation crushed,” In A Nutshell proclaimed. In his narrative Hugh positioned himself as a person who did not fully agree with the way the higher level decisions within the government unfolded, noting that he and his colleagues had come to an agreement with the community and supported their views.

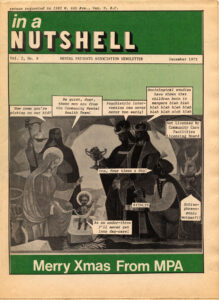

The government plan that was eventually enacted in their neighbourhood was perceived by the MPA as a medically-driven model centering on psychiatric diagnoses and treatment rather than social support based on individual need and citizen involvement. By 1978 citizens’ committees had entirely vanished from the landscape of community mental health in Vancouver, most were only active for two or three years at most. The only analysis of the period to survive is in a 1973 Canadian Dimension article written by then MPA staff person Stan Persky, an MPA staff person at the time, and an unknown coauthor. The cartoon cover of the December 1973 Nutshell included a dig at the community care teams, but a message of loyalty between the new Kits mental health team and the MPA seems to emerge from the pages of the Nutshell. A similar frustration and sense of common purpose came through in the memories Hugh shared.

As researchers looking back through the long rear-view-mirror of more than forty years, we are fascinated by this brief engagement between the newly established Kitsilano Mental Health Team and the local Citizens’ Committee. This group of people – all pioneers in Vancouver’s community mental health system – employed a highly innovative approach to community mental health policy formation in its earliest years, signposting future participatory models of mental health policy-making. Such radical practice should be understood as taking place in an era, a city, and a neighbourhood renowned for grassroots community initiatives and the formation of alternative cultural, social and political systems. Nonetheless, this is a remarkable historical moment which stands as both a powerful illustration of professional accommodation and civic engagement and an implicit critique of “top-down” mental health policy.