Dave Beamish

Dave Beamish was an early MPA member, joining the group in the first months of 1972 or perhaps earlier. Born in Toronto in 1942, Beamish lived with what was then called manic-depression from his late teenage years onwards and had already experienced several hospitalizations when he became involved with the MPA.

The organization rapidly became an anchor in Dave’s life. As he wrote in an extensive Nutshell article two years later, MPA gave him friendship, work, housing and simply a place to go where he would be recognized and greeted with a “Hello Dave.”

Dave exemplified the way MPA offered members the opportunity to develop positive new identities as ex-patients, consumers or experiential experts. At MPA, Lanny and others articulated a new-found, politicized understanding of madness. These insights allowed members to set aside self-stigmatization and avoid seeing their mental health difficulties as a shameful personal failing. Dave found not just a new identity but also a new purpose at MPA. He quickly sought out a variety of paid work the MPA had to offer, successfully running for Drop-In coordinator soon after he became a member. Drawing on their personal experience with mental illness which often included multiple hospitalizations, people like Dave took on the task at MPA of creating new resources for and with their peers. This was a powerful process, and it reshaped both the lives of individual members and the meaning of community support.

Observation and mentorship were other ways in which Dave acquired leadership skills. He said he took note, for instance, that Lanny Beckman always arrived at MPA meetings with a briefcase in hand, prepared to present whatever proposal he wanted to advance. In interviews and his own writing from the period, Dave expressed his firm belief that the empathetic MPA milieu was key to his personal development.

Encouraging and pragmatic conversations with MPA colleague Fran Phillips helped foster the self-esteem necessary for Dave to emerge as an effective activist and advocate. But smaller actions illustrative of the caring atmosphere of the early MPA were also important – like an empathetic note that Beckman wrote to him during a difficult time, and the concerned fellow MPA member who sought a reclusive Dave out by climbing in through Dave’s bedroom window at the West End MPA house. Dave’s trust in his MPA community held when his fellow members had him committed during his 1973 manic episode: writing about this two years later, Dave described his committal as the, “best thing that could happen.”

From its earliest days, MPA set up a system of weekly visits to patients at Riverview Hospital and in the various psychiatric departments in general hospitals. Over time Dave became very involved in this work, identifying as an ex-Riverview patient and supporting patients who were being discharged from the hospital. When the MPA outreach work at Riverview solidified into a funded program in 1977, Dave must have seemed the obvious person for the position of manager.

Dave’s emergence as a public spokesperson for people with mental health diagnoses would have been fostered by MPA general meetings, an aspect of the group that Beckman described as, “Someone would be, after sitting around for maybe a month and saying nothing, would be in a meeting and would start saying something about his point of view, about something that mattered to him.” In the January 1973 CBC documentary, shot shortly after Dave had been elected as Drop-In coordinator, he is a silent presence standing next to fellow MPA member Fran Phillips. By the time the National Film Board arrived in 1976 to make a documentary about MPA Beamish had emerged as a key public voice for the organization, negotiating with Riverview administrators, doing public speaking work with Phillips and publishing in The Nutshell.

As Dave explained, he found his voice at MPA:

In 1977 Dave was involved in filming a CBC “Man Alive” segment about MPA and was elected by the organization to put on a workshop on the MPA model at the national Canadian Mental Health Association meeting. When the CBC was looking for a patient perspective on Vancouver’s escalating housing costs in 1981, Dave was an articulate speaker on behalf of people with mental health difficulties, his concern still on the fate of the patient just re-joining an often unwelcoming community.

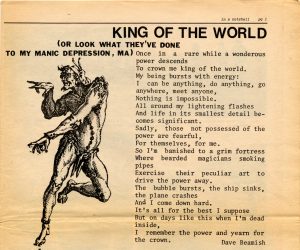

The pages of The Nutshell provided Dave with another way of making manifest his new identity as a mental health advocate with experience: “King of the World” is a rare creative expression of the joy of being manic, while “Sing a Song of Sickness or Who’s Crazy?” states, “I’m an ex-mental patient/ Think I’ll make it my career.” Poetry remained important to Dave for the rest of his life: he deposited a copy of his 2003 collected volume of poems in the National Library of Canada.

Dave talked about both the broader impact of his poetry and its radical mental health message with Megan Davies in a 2011 interview.

Beamish had left MPA by the early-1980s, moving first into the Pioneer Housing project in New Westminster, and then to extensive advocacy work and consumer engagement with the West Coast Mental Health Society and the national and provincial branches of the Canadian Mental Health Association. The confidence, speaking skills, and analytical mindset he had developed at MPA continued to shape his work in these other spheres of engagement: “Don’t social work me,” he once told fellow community expert Jayne Whyte at a CMHA conference.

A budgie or the CMHA? Politician and activist David Reville remembers Dave:

Don’t social-work me! Historian Jayne Whyte remembers Dave:

When Megan phoned Dave Beamish in May 2010 he immediately agreed to be interviewed for the MPA research project. His love for the early MPA was so clear and his anger about how the organization had changed was still strong. He was the only interviewee who did not want the current MPA to have a copy of his interview. Dave participated in the early stages of the Inmates Are Running the Asylum, the MPA documentary, but died in December 2011.