Lanny Beckman

In the fall of 1970, 28-year-old Lanny Beckman was newly discharged from the psychiatric ward of the Vancouver General Hospital and attending a day program at the Burnaby Mental Health Centre. There, the woeful consequences of insufficient professional support prompted the beginnings of a collective response that became the MPA. Lanny’s participation was pivotal, not just to the group’s success, but because he contributed the concept of participatory democracy to the fledgling organization, inserting empowerment into the operational DNA of the group. “Why don’t we see if we don’t need a president? Why don’t we see if we can have a group that is more equal without that?“, he recalled asking at an early meeting.

Connected to both the psych and progressive communities in Vancouver, Lanny brought a toolbox of essential intellectual, media and political skills to MPA. He was also passionately committed to building a better mental health system, but from the bottom up. Supported by the organizational scaffolding and strong community ethos of the early MPA, which Lanny played a central role in creating, members not only challenged the established medical and professional health system but also took the lead in creating new mental health work themselves. MPA therefore made experiential expertise a new cornerstone of community mental health work.

Raised in Vancouver, Lanny was a bright student who went on to study psychology at the University of British Columbia in the early 1960s. Part of a “bohemian” crowd interested in film, art and politics, he took roles in director Larry Kent’s pioneering Canadian films. Lanny encountered radical American ideas about race and student activism as a graduate student at the State University of New York at Buffalo in the mid-1960s, and worked as writer and host for the 1968 CBC television series A Little Learning when he returned to study at UBC.

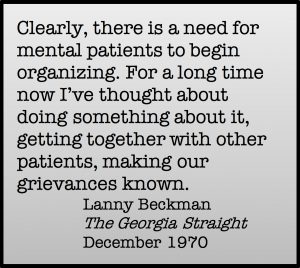

By 1970 mental health difficulties had derailed Lanny’s hopes for a mainstream career, forcing him to seek new life work and reconsider his sense of self. An emerging analysis of the place of the patient in the mainstream mental health system, and of the need for a patient-directed organization was intimately connected to these processes. In December 1970 Lanny published “On the Mentally Oppressed: A Personal Story”, a deeply confessional and strongly political article about mental health in Vancouver’s Georgia Straight, drawing ideas and inspiration from the gay rights, civil rights, feminism and the student movement.

In the months that followed the publication of his Georgia Straight article, Lanny took his fellow patients at the day program to do library research on mental health, reached out to progressive Vancouver Sun columnist Bob Hunter to publicize the new group, applied for funding from the Company of Young Canadians and the federal government’s Local Initiatives Program, and implemented his vision of creating a self-help group based on a model of democratic self-governance.

The times, as Lanny recalled in a 2014 conversation with Marina Morrow, were just right for such an organization.

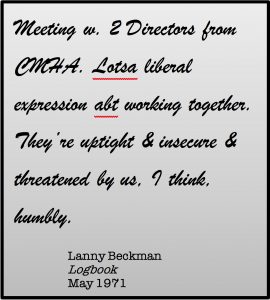

A radical critique of mainstream mental health and a move to build solidarity with other like-minded individuals and groups was an important aspect of the MPA from the beginning. Lanny recorded in his logbook that two directors from the Canadian Mental Health Association office had dropped by at MPA. Noting that the CMHA representatives were edgy and uncertain about the new kid on the mental health block, he went on to give a more positive assessment of “two girls” from a left wing newspaper writing an article about MPA: “Much nicer’n CMHA.” One month later Lanny published an article in The Print Window, a short-lived local publication, calling on MPA to link to new groups like the Insane Liberation Front in New York City.

A radical critique of mainstream mental health and a move to build solidarity with other like-minded individuals and groups was an important aspect of the MPA from the beginning. Lanny recorded in his logbook that two directors from the Canadian Mental Health Association office had dropped by at MPA. Noting that the CMHA representatives were edgy and uncertain about the new kid on the mental health block, he went on to give a more positive assessment of “two girls” from a left wing newspaper writing an article about MPA: “Much nicer’n CMHA.” One month later Lanny published an article in The Print Window, a short-lived local publication, calling on MPA to link to new groups like the Insane Liberation Front in New York City.

The group’s 31st March 1973 protest at Riverview Hospital at a conference on “dangerous patients” was a classic “movement” event and, as Vancouver Sun columnist and MPA supporter Bob Hunter called it, “a historic moment.” For the first time on the North American continent, a group of former patients protested publicly against, “the tyranny of mental institutions,” carrying placards, handing out leaflets and speaking with conference delegates.

Looking back two decades on, Lanny lamented the failed promise of the moment.

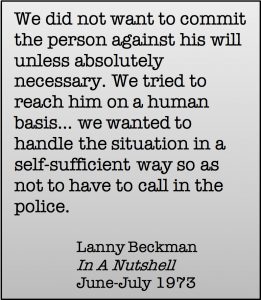

Yet, as Lanny emphasized in his 1995 interview, MPA’s function as a service organization took precedent over its radical politics, a measure of his deep commitment – shared by the group that he began – to provide compassionate support to people in difficulty. How the group dealt with members in emotional crisis is one example of how MPA navigated the borderlands between principle and praxis. This issue was considered important when the group was taking shape in 1971, and Lanny used his graduate school connections with the psych professions to find progressive psychiatrists to train MPA members to deal with mental health crises. Two years later the group called the police when a long-standing and well-regarded member lost control and attacked another member with a knife. Then Dave Beamish went into a frightening manic phase, and his fellow MPA members had him committed to Riverview. This “sobering lesson,” as Lanny described it, is a decision that still troubles the MPA founder, but it illustrates how in day-to-day reality MPA faced difficult dilemmas not unlike those of a professional mental health team.

Yet, as Lanny emphasized in his 1995 interview, MPA’s function as a service organization took precedent over its radical politics, a measure of his deep commitment – shared by the group that he began – to provide compassionate support to people in difficulty. How the group dealt with members in emotional crisis is one example of how MPA navigated the borderlands between principle and praxis. This issue was considered important when the group was taking shape in 1971, and Lanny used his graduate school connections with the psych professions to find progressive psychiatrists to train MPA members to deal with mental health crises. Two years later the group called the police when a long-standing and well-regarded member lost control and attacked another member with a knife. Then Dave Beamish went into a frightening manic phase, and his fellow MPA members had him committed to Riverview. This “sobering lesson,” as Lanny described it, is a decision that still troubles the MPA founder, but it illustrates how in day-to-day reality MPA faced difficult dilemmas not unlike those of a professional mental health team.

Organizational documents of the period show MPA working toward a set of basic practical principles for such moments: the group decided its response to violent situations should be based on first principles of compassion, respect and human rights, but for the collective as well as the individual. Read Lanny’s 1973 Nutshell article, “On Violence and MPA.” As member Geoff McMurchy recalled, individuals exhibiting troubling behaviour at MPA were dealt with, “on a one-to-one basis or internally, I mean without just automatically shipping, calling the police or shipping people off. There was a really strong ethic of meeting people where they are and trying to accommodate their situations.”

Although Lanny and others brought friends and acquaintances like Stan Persky, Barry Coull, Arthur Giovinazzo and Geoff McMurchy into the fledgling association as allies, a shared personal experience of mental health remained the great leveler at MPA. A sense of camaraderie, support and purpose infused the group, as demonstrated in this note about Nutshell layout from Lanny to friend and fellow MPA member Patty Gazzola (nee Servant).

The expression of the personal and the political – analytical, angry, poignant, humorous – filled the pages of In A Nutshell, the newsletter turned tabloid that Lanny began in the first months of the group’s existence. By 1973 the Nutshell’s distribution list had expanded well beyond the MPA membership, and it was being read with interest by mental health practitioners across the city, including the staff at Riverview hospital. A 1973 Nutshell piece by Lanny, “Be the first kid on your ward to start a mental patients organization,” which includes his sister Bonnie Beckwoman’s wonderful MPA cartoons, demonstrates how both humour and analysis were employed to demystify the mental health system and expose its flaws. This too became a hallmark of MPA.

Lanny left MPA in 1975 for a fifteen-year career as editor and publisher of Vancouver’s alternative New Star Press, but the set of beliefs and social movement tactics that he brought to the founding MPA meeting in early 1971 remained cornerstones of the organization over its first decade. His personal engagement with mental health continued, “I’d rather be a tourist in the mental illness world, but I’m not,” he told Megan in 2010. Lanny’s public contributions on the topic of mental health were second hand after 1975, and included his support of the 1988 New Star publication of the seminal Shrink Resistant and a series of articles in This Magazine, Canadian Dimension, and Outlook in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 2010, however, Lanny allowed himself to be lured back into the mental health forum, this time as oral history respondent, then as a historian, filmmaker and editor.