The Provincial Hospital

Name(s) of Institution:

Provincial Lunatic Asylum in (1835)

Provincial Hospital for Nervous Diseases (1904)

Centracare (renamed 1978)

Opened:

1835

Location:

Saint John, New Brunswick

Period of Deinstitutionalization:

1975-1990

Patient Demographic:

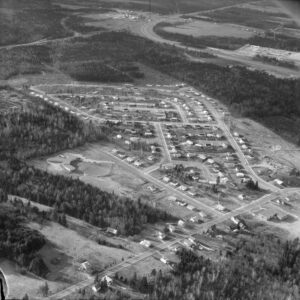

The institution was originally designed for a capacity of eighty, but by the mid-twentieth century, as many as 1,500 patients were in residence at one time. The original building, Canada’s oldest asylum, stood at the corner of Wentworth and Leinster streets in Saint John. In 1848, both male and female patients began to be transferred to a new building in the parish of Lancaster. The wards at the Provincial Hospital were divided both by sex and by socioeconomic ability; those who could pay had better accommodations and, likely, more extensive treatment.

Deinstitutionalization:

The first Provincial Division of Mental Health was created in New Brunswick in 1949. In a 1953 review, the Division’s stated goal was to treat patients whose mental health difficulties were considered “mild” outside the mental hospital, signalling a shift to community mental health. Public education was considered to be an important element of this process.

In 1954, the 225-bed Campbellton Provincial Hospital (later named Restigouche Hospital Centre) was built at Campbellton, in part as the result of a commission of inquiry conducted nine years earlier into patient conditions at the Saint John facility. The creation of this new institution on the cusp of the de-institutionalization era was a reinforcement of institutional values and beliefs. Patients were transferred to the new institution from the main hospital in Saint John.

Patient numbers at the Saint John institution steadily increased through the 1940s and early 1950s to peak at 1,697 in 1954. From 1955 forward, in spite of a continuing decline in the number of patients resident at the Provincial Hospital, overcrowding continued into the 1960s. “It is practically impossible to give what is considered good modern care,” the superintendent declared in reference to overcrowding in his 1962–63 report.

At the same time, early moves toward readying patients to live outside institutions and supporting them in a transition to community living were beginning at the Provincial Hospital. Its 1947 annual report noted the need for follow-up work conducted by a trained social worker with experience in the psychiatric field. A somewhat experimental aftercare program of the late 1950s conducted regular checks of recently released patients and assisted them with “problems of adjustment.” In the 1958–59 administrative year, seventy-three patients participated in the program. In 1960, a “Remotivation” program was begun; it was a nursing service project that grouped staff members with small numbers of patients to read and to discuss aspects of daily life. Two years later, the Chief Psychologist at the Provincial Hospital reported that group therapy was continuing alongside opportunities for certain female patients to meet with staff members and discuss feelings of depression, anxiety, and personal insecurity. Like Remotivation patients, this patient cohort was destined for rapid release from hospital care.

In 1968, the report of the Study Committee on Mental Health Services in the Province of New Brunswick was published, and new provincial legislation covering mental health was introduced with the aim of reforming psychiatric care to provide care in the community rather than in institutions.

By 1976, there were 533 patients remaining in the facility. Renamed Centracare two years later, the former Provincial Hospital took a clear move toward de-institutionalization and community mental health. The board of medical directors was augmented by a set of directors drawn from the community and, over the next decade, the patient population shrunk a further 39 percent to 283 persons.

Following a program to upgrade patient care and staff education, Centracare made a successful 1981 application for accreditation. At the same time, it was clear that the aged 1848 facility was not suitable for late-twentieth-century mental health care. By the mid-1980s, a shift to emphasize the community potential of the facility had taken place. The volunteer-led Image Committee began hosting open educational programs on topics like Death and Dying and Behaviour Relations, and staff were encouraged to present Centracare to the broader Saint John community. However, a 1986 study of regional mental health services delivery argued against ongoing de-institutionalization, maintaining that there was a need for a centralized psychiatric hospital in the province.

In 1988, the Mental Health Commission of New Brunswick was created, setting into place a “Ten Year Plan” which included a strong push to close Centracare beds and move many more patients out of the facility. Both staff and members of the broader public voiced concerns that former patients were not being adequately supported in the shift to community living. Centracare closed its doors for good in 1996 and the property was purchased by J.D. Irving Ltd. and turned into a park. However, a new twenty-first-century psychiatric hospital offering medium- and long-term psychiatric services will open in Campbellton in 2014, signalling the ongoing life of the psychiatric institution in the province of New Brunswick.

Transinstitutionalization:

From January 1950, local mental health clinics were established in urban centres of the province, first in Saint John and later in Moncton and Fredericton. By 1954, all were full-time operations with a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, a psychiatric social worker, and a clerk stenographer. These clinics became sites for testing the mental capacity of children, using the public school system to filter in youth. The first day school for children labelled “mentally defective” was set up at the Saint John Mental Health Clinic.

Community mental health clinics were also envisioned as sites for tracking adults’ mental health histories, with the Social Service Department taking a central role in coordinating support from family members, voluntary agencies, and professional agencies. The Superintendent’s 1958–59 report called for shared hospital–clinic patient information and a tightly coordinated follow-up of community mental health patients.

Another important step toward trans-institutionalization was the 1953 establishment of a space for eleven psychiatric patients in the new Moncton Hospital. By 1960, there were psychiatric units in the two general hospitals of Saint John and Moncton and a fourth mental health clinic in Edmundston. There was also a White Cross Centre in Moncton, set up by the Canadian Mental Health Association as a social space for former patients to find community.

Work Therapy into Occupational Therapy:

From the beginning, work therapy was an important aspect of patient life at the Provincial Hospital. By the latter nineteenth century, the institution had purchased a farm on Sand Cove Road. Compulsory male farm labour was considered beneficial to mental health, and a building was constructed on the farm site to house residents assigned to farm chores. Male patients also laboured in asylum workshops, the first of which was built at the Lancaster site in 1880. Female patients worked as seamstresses, making clothes for other patients and likely performing other gendered institutional work. But this work “therapy” was, in fact, clearly a part of the institutional economy: paying and nonpaying patients were separated, and able-bodied nonpaying patients worked in various institutional locations.

Institutional reports of the 1950s show a shift from work therapy to occupational therapy with the introduction of limited vocational training for patients. But early occupational therapy at the Provincial Hospital also included a varied set of recreational activities that ranged from making kiln-fired pottery or playing tennis to visiting the burgeoning institutional library and attending picnics on the grounds. In the hospital’s 1950 annual report, an occupational therapist appears on the list of Heads of Departments for the first time. Her name was Martha Conn. By 1958, the program had a budget of nearly $7,000 and merited a separate report in the annual institutional account.

The Sand Cove Road farm ceased operation in 1970 and the property was sold. An institutional historian cites dwindling patient interest in performing physical labour as a factor in this administrative decision.

Patient into Person:

Very early institutional reports from the late nineteenth century hint that some efforts were made to treat the patient as a whole person, but such practices were likely restricted to paying and/or “high-functioning” patients. During this period, for example, patients were apparently permitted to attend a nearby church in the company of an attendant. The first picnic for patients was held in the summer of 1882 and a practice of giving patients Christmas presents followed in the early 1900s.

Not until the 1950s, however, do we see a clear institutional willingness at the Saint John institution to facilitate the participation of mental health patients in activities routinely enjoyed by the general public. By 1954, weekly movies were being presented for patient viewing. Four years later, the hospital’s Occupational Therapy Department was offering films, dances, games, concerts, and bowling, all with the stated aim of getting patients off the wards and, to quote the annual report for that year, “less confined and consequently less resentful of hospital life.” The occupational therapy report for 1958–59 notes as well that there was now a television on every ward and that a patient library totalling 3,000 books had been created by CMHA volunteers, a group that appears to have played an important role in such patient-centered initiatives at the hospital. By the 1960s, the CMHA had set up monthly patient birthday parties and the giving of Christmas gifts.

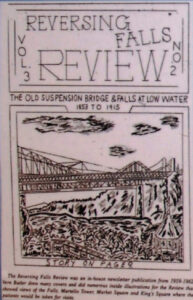

From 1959 to 1962, the Reversing Falls Review, a patient-published newsletter, was published in the Occupational Therapy Department of the hospital. Patient submissions included testimonials, poetry, and artwork, though submissions were subject to administrative approval. Reversing Falls Review was followed in 1977 by Echoes, which was published until 1981.

In 1945, an investigative reporter from the Montreal Standard newspaper went undercover as an attendant at the Provincial Hospital. The riveting and horrific tales of patient neglect, unsanitary conditions, and patient abuse chronicled in his account resulted in a 1945 provincial commission of inquiry into the establishment. The commission exonerated the institution’s current Superintendent, deemed the newspaper coverage the work of a sensationalist press, and noted possible links between the reporter and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation political party and criminal elements. Nevertheless, the medical doctor investigating the hospital on behalf of the commission found serious overcrowding, a dangerous shortage of staff, routine use of chemical and physical restraints, and evidence of vermin. The final commission report recommended a new building and a staff-to-patient ratio of 1 to 8 that included a greatly increased number of professionally trained nursing staff.

But overall, institutional histories and reports of the Provincial Hospital devote little space to the consideration of fundamental patient rights and evolving staff attitudes toward patients. In 1958, the Superintendent’s report noted efforts to limit the use of restraints on “too active patients” and described a new program in which a group of “the most deteriorated and regressed” patients were taken off the ward on a daily basis for activities. The resulting changes in the behaviour of patients considered chronically ill were, he wrote, “a revelation to many of our staff.” However, the 1958–59 report makes clear that patients who could not communicate fluently in English were excluded from such initiatives. At the close of the decade, the Superintendent reported that some wards were now kept unlocked during daytime hours, and a parole system had been established to allow selected patients free access to the hospital grounds. Patients were rarely restrained or kept naked or in dirty or torn clothing, they no longer had to eat institutional food with their hands or a large spoon, and routine inspections had banished rats and cockroaches from the wards. All of these changes were emblematic, the superintendent argued, of a new program of “liberalizing and humanizing” the institutional treatment of people whose mental health issues were considered chronic. It should be noted, however, that these points also addressed issues raised by the 1945 commission.

It was not until 1987 that patients in New Brunwick’s psychiatric hospitals were given the right to vote in provincial elections.

The rights of French-speaking Acadian patients at the Provincial Hospital, and in particular their right to care and treatment in their own language, is only alluded to in annual reports and official histories. However, the case of a Francophone inmate from Balmoral who was allegedly beaten to death in the 1940s by inmates or staff after refusing to have his birthday celebrated in English, and the evident exclusion of non-English-speaking patients from more progressive therapy regimes, suggests a clear and troubled cultural divide within the institution.

Staffing in the Deinstitutionalization Era:

Although the institutional history of the Provincial Hospital stresses the important role of nurses in psychiatric care in the 1950s and beyond, the evolution toward community mental health is reflected at the facility in an increasingly diverse professional staffing profile. By 1948, there was a part-time dentist, and two years later, an occupational therapist is mentioned for the first time. By 1955, three social service workers (social workers) and a psychologist were also on the hospital staff list. Three years later, there were five British psychiatrists and sixteen physicians working at the hospital, and there was a plan to hire a bilingual psychologist who could communicate with French-speaking patients.

A desire for enhanced nursing training is a constant refrain in the Superintendent’s annual reports of the late 1940s and beyond. In 1948, he noted that a psychiatric nursing instructor would be helpful in training staff for the province’s psychiatric facilities. By 1952, a Department in Nursing Instruction was being developed to train new and existing staff, and a course for Psychiatric Nursing Assistants was being offered. In 1962–63 an Affiliate School for Psychiatric Nursing was opened, linked to the University of New Brunswick, and contracted to offer an eight-week training course for undergraduates from most provincial schools of nursing. Student nurses, it was observed, were very helpful in patient “re-socialization” on the wards.

There were difficulties in keeping nursing staff at the provincial facility throughout the post-war period. In the early 1960s, nurses were pulled away from the asylum to work in other health facilities that offered higher pay and eight-hour workdays. This situation was rectified in 1965 when an eight-hour workday and forty-hour workweek were established at the Provincial Hospital.

Staff shortages were also a major problem in the burgeoning occupational therapy (OT) program at the hospital. OT program administrators from the late 1950s constantly noted the difficulties in finding OT staff willing to work for fees lower than those set in the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy’s pay scale.

In the 1970s, a flattened administrative and staff hierarchy allowed for innovations in occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work, and nursing care. The value of gaining further professional training was emphasized, and psychiatric attendants were given the opportunity to train as registered nurse assistants or registered nurses. Staff working as registered nurses were encouraged to obtain a Bachelor of Nursing. Affiliation with Dalhousie Medical School brought young doctors into the field of psychiatry

Institutional reports indicate an engagement with the process of preparing nursing staff outside the hospital to work in community mental health nursing. The 1958–59 Superintendent’s report details a course offered to public health nurses to help them in their work supporting former patients and their families in the period following discharge. Similarly, the 1962–63 Social Service Report noted the need for continuity of social work care for patients moving from institution to community, particularly in maintaining contacts between social workers and family so that progress made in hospital would not be lost.

Sources:

Crawford, David. “Canadian Hospital Histories—Atlantic Provinces.” Histories of Canadian Hospitals and Schools of Nursing. https://internatlibs.mcgill.ca/hospitals/hospital-histories3.htm#NB.

Goss, David. 150 Years of Caring: The Continuing History of Canada’s Oldest Mental Health Facility. Saint John: MindCare New Brunswick, 1998.

LeBlanc, Eugène, and Nérée St-Amand. Dare to Imagine: From Lunatics to Citizens. Moncton: Our Voice/Notre Voix, 2008.

New Brunswick Museum.

Province of New Brunswick. Report of the Royal Commission Inquiry: The Provincial Hospital. Province of New Brunswick, 1945.

Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, RS 140. Reports of the superintendent. Centracare Saint John Inc.

St-Amand, Nérée. Folie et Opression: L’Internement en Institution Psychiatrique. Moncton: Les éditions d’Acadie, 1985.

Vitalité. “Restigouche Hospital Centre.” Vitalité. https://www.vitalitenb.ca/en/points-service/restigouche-hospital-centre (accessed June 16, 2014).