The Asylum for the Insane, 1886

Location

Selkirk, Manitoba

Present Name

The Selkirk Mental Health Centre

The Site

The Asylum for the Insane,” in Selkirk, was the first psychiatric facility built for that purpose on the Canadian prairies. It was constructed in 1886 to serve the entire prairie region and the northern forests and Canadian Arctic west of Hudson Bay. The Selkirk hospital is on perfectly flat land. In 1885 it was a bog, surrounded by grassland.

Originally the hospital was separated from the community by farmland. Housing and other developments are now close to the hospital on three sides. Farmland is visible only to the west. Now known as the Selkirk Mental Health Centre, the buildings retain their congenial physical and aesthetic relationship with the City of Selkirk. There are no fences, hedges, or windbreaks to separate them from the community.

Architectural and Service Details, 1886 Building and Additions

| Architect | Samuel Hooper, Provincial Architect |

| Builders | Wood and Mitchell |

| Floor area | Approximately 100,000 sq ft, including basement and additions. |

| Height | 4 storeys including basement |

| Description | Monolithic, both 1886 and 1923 buildings, shallow “H” plans. |

| Occupancy | 167 (Phase 1 only), 1880s Design (Isumi, 1966) |

| Structural | Masonry bearing walls, probably wood frame floors and roof in 1886. Stone foundations to ground floor. 1911 additions built, “as nearly fireproof as possible” (D.B., 1976) |

| Heating | Steam boilers to coils and forced war air to all rooms. New power plant improvements in 1903 and 1909. |

| Lighting | Electric, steam-driven generators. |

| Water supply | An ample supply of water was found, supplied by well 275 feet deep. |

| Plumbing | Sewage was piped to the Red River a few miles to the East. |

| Fire History | None noted in hospital history or by Hurd. |

The Buildings

“The accommodation of the asylums at Selkirk and Brandon is taxed to its utmost capacity,………applicants are waiting their turn for admission.” Henry M. Hurd, 1917

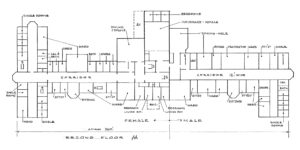

The 1886 building was planned with a greater number of private rooms and small wards than any other western asylum. Its plan was based on the work of a Pennsylvania commission studying housing for the insane (Selkirk Mental Health Centre, 1986). Plans show only two small “sitting rooms” on each floor. There are no large dormitories or day-rooms. Corridors were approximately 12 ft wide. They were adequate for service traffic and for walking as patient exercise. The floor plan showed a “glazed balcony,” approximately 15’X40′, which was enclosed in winter and netted in summer for use as an airing verandah. According to one annual report, the attic was, ”large, roomy, and well lighted.” Its use was not specified, but likely it was a dormitory under crowded conditions. Lighting was electric, and on the prairies steam heat was essential.

The floor plans of the Selkirk and Brandon facilities show that the two Manitoba hospitals had a majority of single rooms for patients, with high levels of patient privacy. Previous Ontario practice, possibly a precedent for Manitoba designs, favoured single rooms and small wards until 1904.

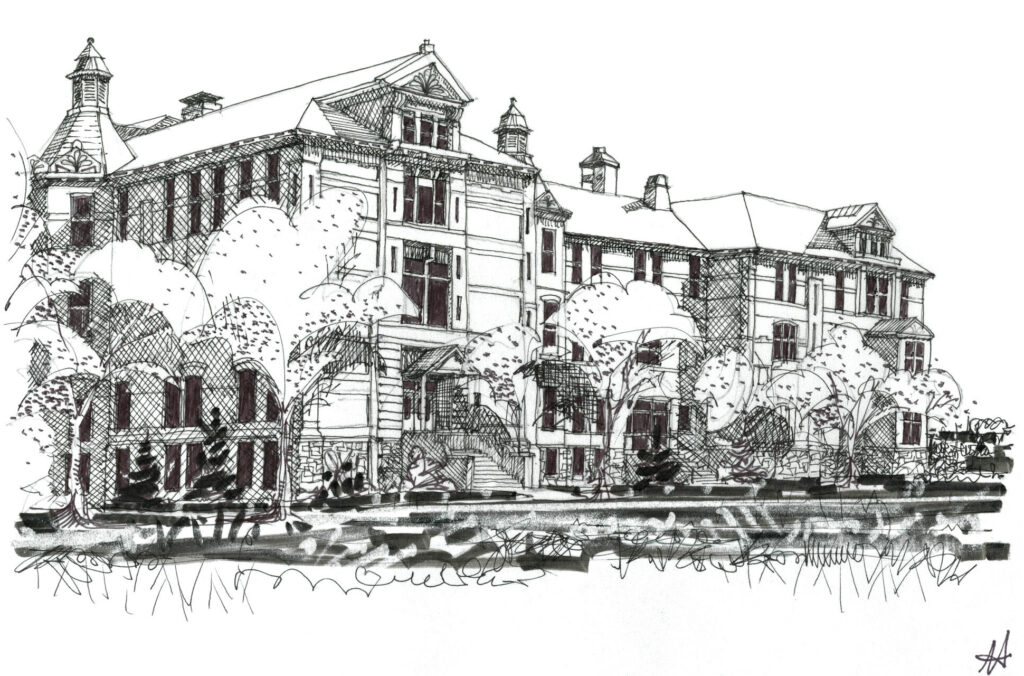

The 1886 asylum in Selkirk was an imposing structure designed in an eclectic manner with light touches of small neo-classical gables, turrets, and lanterns on small roof elements. Entries and external stairways were generous, with prominent detailing. Throughout the life of the hospital, additional buildings were added to the site, including the present main building opened in 1923 and now used for acute patient care. It was at first named “The Reception Unit,” or “Soldiers’ Pavilion,” and dedicated to the care of veterans of the First World War. Funds for its construction came from the United Kingdom in gratitude for Canadian military assistance during that war. The Reception Unit was designed in Scottish Baronial form and is the most faithful to style among Western Canadian mental hospitals. Plans for this building show attractive solariums and recreation rooms on each upper floor, one on each side of the administration block. That feature was unique, and presumably for the benefit of honoured veterans. It was not included in the planning of any of the previous or later buildings at Selkirk or any other site.

A school for nurses’ training was established at Selkirk in 1920, and a nurses’ residence was built in 1926. It has now been converted to administrative use. The original asylum was demolished in 1978. For patient care, the Health Centre now uses the 1923 building for acute care and rehabilitation, and a second large building as a geriatric facility.

The Selkirk Asylum opened in May 1886, providing 167 beds. 59 patients were immediately moved in from the Stoney Mountain Penitentiary. Crowding soon developed as others followed. Some patients were temporarily sent back to the prison. The hospital was filled again within 4 years, and in 1890 a few quiet patients were transferred to a Home for Incurables at Portage la Prairie. Dr. David Young, first medical superintendent of the Selkirk hospital, noted in 1904 the need to place some patients on cots in corridors. A History of the Selkirk Mental Health Centre notes that in 1904 patients were bedded in the corridors on straw mat “shakedowns.”

Grounds, Farms, and Gardens

Soil nurtured by buffalo grass and prairie fires was fertile and were free of stones, or excess water was easy to prepare. On good or poor soil, frost and drought slowed the growth of trees for decades. Land west of the town of Selkirk was swampy, part of it labelled “The Big Bog.” Timothy Byers (a nursing assistant in Selkirk) feels that the bog is now known as Oak Hammock, a popular place for viewing waterfowl, and headquarters for Ducks Unlimited. The high water content of the soil produced an artesian well adequate for gardens, landscape and livestock. The hospital helped with water control in the bog by building a piped system to the nearby Red River.

Patient Life

The Selkirk and Brandon asylums started operations based on practices then in effect in Ontario. In 1896 a new building was constructed at Selkirk for multi-purpose use as a chapel and amusement hall. In 1898 Burgess noted a combined population of 325, under treatment without physical restraint. Work and recreation were used as therapy from the start of operations. In his CNCMH Survey report of 1918, Clarence Hincks recommended development of occupational workshops. Products were to be sold in Winnipeg by arrangement with the T. Eaton Company.

In 1898 Burgess noted that agricultural work was the primary method of occupying patients’ time. Under Dr. Young, the Selkirk Asylum from the beginning engaged capable patients in work for therapy and production. Following common practice, men worked the farm, gardens, and greenhouse. Women were engaged indoors on domestic work. Large plots of land were laid out for farming by patients, stables were built for cows and horses, and two barns sheltered swine. Cows from Selkirk were taken to the Brandon Winter Fair and won numerous prizes.

The Selkirk hospital was initially enclosed by a perimeter fence placed for security and to keep patients out of sight. It was 8 feet high, constructed of wooden pickets, and 3000 feet in length. In 1926 it was removed. Airing yards close to the buildings were fenced and secured and remained in use for decades. Lorna Weiss, a current librarian in the hospital, remembers a miniature golf course on the site, of uncertain date. It was removed and replaced by a building in the enlargement of hospital facilities.

Sources

T.J.W. Burgess. Presidential Address to the Royal Society of Canada, Transactions, Section IV, Geological and Biological Sciences, 1898.

C.M. Hincks. “Survey of the Province of Manitoba,” Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene, vol.1, 1919-1920.

Henry M. Hurd. The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1917.

No author. A History of the Selkirk Mental Health Centre. Selkirk, Manitoba: Selkirk Mental Health Centre (1986).