The Saskatchewan Provincial Hospital, 1914

Location

North Battleford, Saskatchewan

Present Name

The Saskatchewan Hospital

The Site

Saskatchewan began the planning of its first mental hospital in 1907, but due to long debate and competition from various communities, the Saskatchewan Provincial Hospital did not open for service until 1914. The site chosen in North Battleford was and remains impressive, on rolling farmland above the valleys of the Battle and North Saskatchewan Rivers. The region undertakes grain and mixed farming in an area of parklike natural vegetation.

The hospital is located on a level bench above the north bank of the river. The sloping front lawns of the buildings, with south exposure, provide welcome shade trees and views of the river and farms beyond. The building has a southern exposure, excellent views to the valleys and farmland beyond, and is now sheltered by windbreak trees with extensive lawn and garden areas. Its location and image remain as a prairie island, with open space separating it from the communities of Battleford and North Battleford, as initially intended.

Architectural and Service Details

| Architect | Storey and Van Egmond, Regina |

| Floor area | 174,000 sq. Ft. including the basement and partial 4thfloor |

| Height | Approximately three storeys including basement, except four at centre block |

| Description | Monolithic, linear, numerous “cross blocks” for dormitory space. |

| Cost | $1,000,000 approximately in 1914 |

| Occupancy | Designed for 1174, Max occupancy 1716, in 1945 |

| Structural | Fire resistant. Brick bearing walls, reinforced concrete floors and beams. Exterior walls brick finish. |

| Heating | Coal-fired high-pressure steam to the kitchen, laundry, sterilizers. Low-pressure radiation inwards. Electrical fans move fresh and exhaust air through the duct system. Powerhouse and laundry built in 1913. |

| Lighting | Electric, from steam-driven generators. |

| Fire history | No serious fires noted in hospital history. Fire rated doors in corridors separate ward units. |

The Buildings

“The housing of classified patients in their diverse units is well arranged for. The units of each wing (Viz, Acute, Observation and Chronic) are complete in their entirety, each having dining rooms, exercise rooms, bathrooms and dirty rooms in the basement. Disturbed units are well arranged ensuring a quietude to patients in other wards.” ~ from Delores Kildaw, 1991

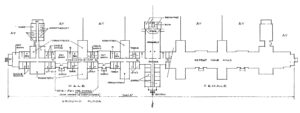

Architecturally the main buildings are typical of well-built brick buildings of the time, with no obvious stylistic image involved. The architects had visited New York institutions before planning the North Battleford building. Its concept is unusual in its length and linear simplicity. The floor plan is based on a very long double-loaded corridor, with the only daylight and natural ventilation to the corridor provided second-hand at the day-rooms that are open to the corridor. The total length of the corridor is not apparent due to closed doors at each cross-block. The doors provide separation of ward units and divide the building into fire compartments. The corridors are wide enough for walking exercise, but the doors limit walking to the length of each ward section. All weather access to end wards was compromised by the linear plan. In fine weather staff could walk outside, using the separate entries to each ward block. In wet or wintry weather all traffic was required to pass through a sequence of wards, no matter what the destination. Control of patients during routine hospital movements would have required extra attention at times.

The original design called for 52 beds on each floor in single and double rooms, and many more in large dormitory spaces. A central administration block separates the building into wings, one for male, one for female patients. The plan of the long building shows separate entries to the front of each ward section, opening from landscaped grounds. Drawings do not show rear exits to male and female airing courts from each ward. They are noted on descriptions of the ward functions. The construction of this first hospital building was badly managed, resulting in an investigation by the Haultain Royal Commission which investigated tendering procedures and patronage.

The length and size of the building responded to population growth in Saskatchewan before World War One. A higher building of this length would be imposing; as it is the low profile and small-scale cottage roof detailing soften the picture. Henry Hurd, in 1917, described the healthful and pleasant site, and the attractive and well-built building. The North Battleford News, February 5th, 1914, described the new hospital as, ”our own costly state home.” Hurd noted excellent ventilation of the wards and high-quality drinking water from an artesian well. Utility water was taken from the river. A high and naturally lighted basement provided space for dining rooms, bathrooms, exercise rooms, and rooms for incontinent patients. Hurd noted separate access to, ”spacious airing courts,” one for each sex.

A wing for tubercular patients was added in 1919 and used as such until the disease was finally brought under control. According to Kildaw, construction activity on additional structures was stopped in 1930.

The first staff houses were tents and make-shift shacks on the riverbank. Six houses for medical and administrative staff, with grounds for family use, were constructed in 1916. Most employees continued residence in primitive housing, built at random on the grounds. Seventeen more houses were provided in the 1920s. The developed site was and remains attractive and well maintained. Early staff residences are now used for incidental functions.

Grounds, Farms and Gardens

“It was a good life for the staff members and, in many ways, for the patients. They also were a part of the social structure and had meaningful and rewarding work and a chance to show their skills, and to bond with the animals they looked after.” ~ from Delores Kildaw, 1991

When the hospital opened in 1914, forty acres were seeded to vegetables; barns and livestock soon appeared. By 1916 the site included a large farm of 2300 acres (3.59 square miles) of good land, some of it in the river bottom. Development included barns, stables, and piggeries. From the start of operations, male patients worked the farm and gardens. Farm labour by capable and fit patients was standard practice at North Battleford. Activity, fresh air, and enjoyment of animal care in the livestock sections were thought to be highly therapeutic, especially for the many patients who were farmers. In 1916 there were ten hired staff, plus patients, using horse-drawn equipment to break and work the land. Male patients working at this kind of hard physical labour were called, “the stone gang.” Drawing of coal by horse and wagon, and loading with hand shovels was eventually eased by a spur line from the railway delivering coal and other supplies direct to hospital bunkers and storehouses.

Revenue from the farm and gardens in 1926 was $ 43.561.00. During the drought of the 1930s, bottomland at the river was cleared, broken, and planted for market garden production. That operation was known as the Irrigation Farm. It stimulated high interest among dryland farmers in Saskatchewan. Irrigation by ditches was later improved with a sprinkler system. The operation was vital for hospital supply in the Depression, and excess fruit was sold to drought-stricken farmers on higher land. The orchard at the Irrigation Farm produced raspberries, strawberries, gooseberries, and crab-apples. Surplus fruit and other produce were sold; crab-apples were popular with local residents.

Farm operations continued to expand on the North Battleford site. In 1936 there were 68 hired farmers directing the work of patients tending the farm, gardens, and livestock and poultry sections. A farm manager directed the operations, hired foremen supervised the various crews, and medical staff and attendants were always on hand. Ribbons were won in livestock competitions for horses, cattle and swine. Purebred Yorkshire hogs were raised and auctioned each year to farmers in the region. Poultry and swine operations were relocated to the valley, and in 1941 287 male patients were moved into a four-story building erected for them at the Irrigation Farm. In 1946a herd of Holstein cows was sold to the Weyburn hospital to augment its dairy operations.

The extensive flower beds shown in photographs from the Saskatchewan Archives Board indicate that cultivation of flowers at North Battleford occupied many patients as it did at other hospitals in Western Canada. In 1945 the gardens produced 7296 potted plants for delivery to the wards. There were 20,000 annuals, 1000 tubers and bulbs, and 5000 other plants in scattered beds. Patients were permitted to select and care for specific cold frames in the gardens. Kildaw comments in her history of the institution that many patients worked small private gardens, and sold produce at the hospital’s annual bazaar.

Sheila Kelly, now a retired child clinical psychologist, was born and raised in North Battleford and worked in the hospitals in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, and Oliver, Alberta during and after her studies at the University of Alberta. She did not work in the hospital in North Battleford, but her childhood memories include family drives in the evening to visit the grounds, farm, and gardens of the institution. Sheila has a cousin still in North Battleford who confirms public interest in the agricultural work of the hospital, especially the irrigation farm. In the drought of the 1930s, irrigation was widely advocated on the prairies but seldom seen.

Immense dahlias flourished outside the greenhouses, which were, ”an inspiration to local gardeners.” The farm raised pigs, cows, chickens, and horses. Pigs were Sheila’s favourites. There were a few exotic birds and for a short time an enclosure with deer. The fenced orchard experimented with the development of frost-resistant apples. Sheila writes that she remembers no fear of patients while she visited, and notes that in the 1960s, ” the town was truly up-in-arms at the thought of the farms and gardens being done away with.” The benefits of work for patients could still be available, according to Sheila, if they could be paid for their work.

Delores Kildaw is silent on the matter of outdoor recreation. Her only comments in this area note that lawns, golf course, and tennis courts were constructed and maintained by working patients. In 1913 Dr. J.W. MacNeill was appointed as the first superintendent of the hospital. One of his first acts, apparently before construction of the hospital was completed, was to order demolition of a high walled airing court. In spite of that action, the courts persisted. A hospital survey by CNCMH in 1918, and again in 1920, complained about the continued use of airing courts, ” the bare and dreary apology for recreation grounds.” Throughout his long career CNCMH inspector C.M.Hincks attacked airing courts as makeshift structures for the convenience of lazy members of hospital staff. His opinions were countered by concerns about staff shortages. In the instance of North Battleford, Hincks sympathized with the need for high walls in prairie winds and the absence of sheltering trees. Growth was slow on the sandy soil of the region, and he expressed hope that time would solve the problem. According to the CNCMH report of 1920, the continued use of airing courts was, ”the one objectionable feature at Battleford,” and would be quickly resolved.

Institutional Life

“The patients were served a lot of dry beans and peas and, at supper, they were often served Sunny Boy cereal. They were served all their food, even dessert, at once in an aluminum bowl, and they had to eat with their hands.” ~ from Delores Kildaw, 1991

On February 4th, 1914, the first 347 patients arrived in North Battleford aboard a special train from Brandon, Manitoba, where they had previously been confined. The temperature was 60 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit. Twenty-three nurses and attendants from North Battleford supervised the trip. After the journey, four patients died, apparently exhausted by the excitement of the transfer.

In 1918 the North Battleford hospital was inspected by C.M. Hincks of the CNCMH, assisted by Major C.B. Farrar, the latter acting on behalf of military authorities caring for soldiers returning from World War I. Hincks and Farrar praised the charming site and the well- constructed building, but due to wartime conditions found it so overcrowded, ” that the officials cannot be expected to produce the best results.” They approved of a general duty nurse for the physically ill and found the building to be well kept. Quiet wards were attributed to the effective use of ten continuous hydro-therapeutic baths.

A Mental Hygiene Survey of the Province of Saskatchewan followed in 1920. The 1920 survey was pleased with the improvement of Occupational Therapy and urged a special industrial building for further development. In 1930 CNCMH published its next inspection of North Battleford. It noted that there were excellent provisions for games and exercises, and for outdoor life without the use of airing courts. In later reports of 1937 and 1945, Dr. Hincks was increasingly concerned with the severe overcrowding of both Saskatchewan institutions and paid little attention to recreation.

Before the use of drug treatment, the noises of troubled people could be heard outside an asylum building. Leo Belanger shared this memory of a visit to North Battleford institution, “When you came here in the summertime, and all the windows were open, it was like driving up to a beehive. There was a constant moaning from the patients; the whole building hummed.”

Sheila Kelly’s recollections of relations between the hospital and community are positive. Some staff, usually physicians or supervising nurses, took patients to their homes and gave them work in their houses and gardens. A few families were willing to provide home care for a patient well before the community system was developed in the 1960s. Sheila notes that the depopulation of the hospital began in the early 1980s, and early retirement was offered to nurses. She was advised that at that time the educational level of nurses was low; staff training had ceased 20 years earlier.

The CNCMH survey of 1920 noted that amusements for patients were varied and well arranged. The report suggested that a future building for occupational therapy might include provision for amusement functions. Hospital staff worked 12 hours a day, 6 days a week. Two hours extra “dance duty” was required on Mondays, and two hours on Wednesday for attendance at the picture shows. No overtime pay was provided. In the early years, there were active shops for toy and cabinet production, with sales at an annual bazaar and dance celebration.

Sources

Harley Dickenson. The Two Psychiatries. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1984.

C.M. Hincks. “Mental Health Survey of the Province of Saskatchewan,” Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene, vol.2, no.4, 1920.

Henry M. Hurd. The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1917.

Delores Kildaw. As History of the Saskatchewan Hospital, North Battleford, Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Prairie North Health Region, 1991.

Under the Dome: The Life and Times of Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, Ane Robillard, ed. Weyburn, Saskatchewan: Souris Valley History Book Committee, 1986.