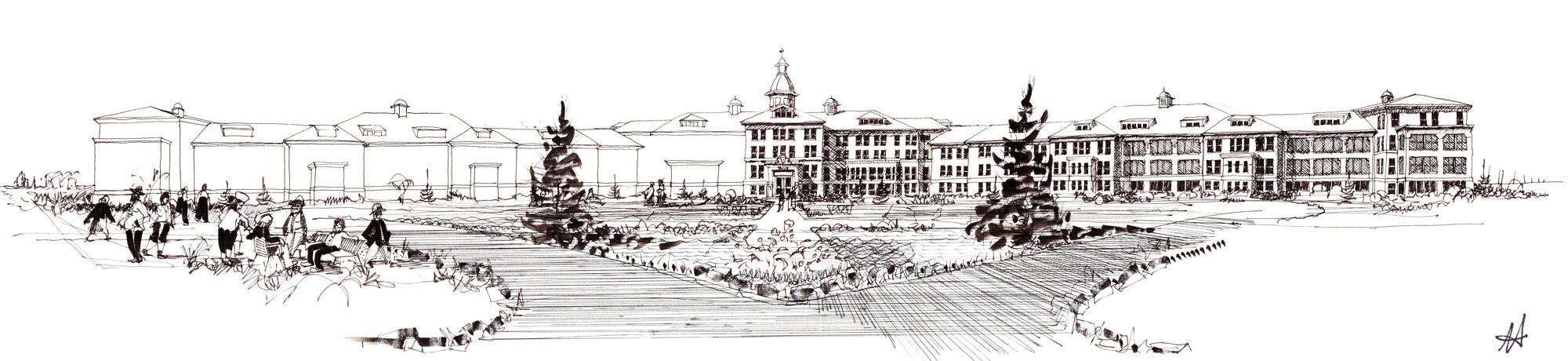

The Weyburn Mental Hospital, 1921

Location

Weyburn, Saskatchewan

Subsequent Names

Renamed Saskatchewan Hospital, 1947

Renamed Souris Valley Regional Care Centre, 1971

The Site

“If I live to be a hundred I’ll never forget those Depression dust storms. The floors, the bed sheets our uniforms, everything would be covered with black silt. We tried to block the windows with wet towels but nothing helped. It was pure misery for the staff and patients.” ~ from Under the Dome, 1986

The Weyburn Mental Hospital was on flat, high-quality farmland, with a few strangely isolated round hills within sight. A slow and meandering stream, the Souris River, flows through the old hospital grounds. It is the river of “The Mental Hole”, a place for summer swimming described by W. O. Mitchell in stories of his childhood in Weyburn. In the 1930s drought, the dry stream bed offered no water for swimming or for the hospital gardens.

The Souris River at Weyburn is a shallow, meandering stream, with low banks. The slope of the flat land to the stream is virtually undetectable. Native growth was entirely grass, except for sparse clumps of shrubs and willow at the river. Weyburn is located in the south-east portion of Saskatchewan, and of all prairie, asylums were the most exposed to drought and dust storms. Water in the Souris River dried up in some years, and wells were not reliable. In 1946 an existing reservoir seven miles south of Weyburn was taken over by the provincial Department of Public Works. By 1948 it was supplying the hospital and the town.

All prairie asylums suffered from dust storms in the 1930s. Weyburn was the worst hit; its location in the dust bowl of Southern Saskatchewan, and the air leakage of sliding wooden sash of hundreds of windows made life miserable for staff and patients.

Architectural and Service Details

| Architect | M.W. Sharon, Provincial Architect |

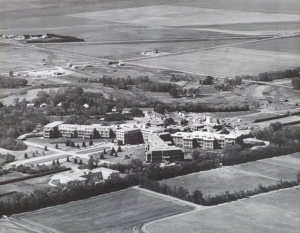

| Floor area | 342, 000 sq. ft, 3 wings, excluding TB Annex and Power House |

| Height | 3 storeys at wings, 4 at administration building including basements. |

| Cost | $2,000,000 (Phase 1, admin block plus 2 wings) (117) |

| Description | Monolithic, axial symmetry of radial wings and centre block. |

| Occupancy | 1040, (3 wings), excluding TB Annex added in 1937. |

| Structural | Fire resistant. Steel frame, brick walls, concrete floor slabs, including the attic. Woodroof framing. |

| Heating | Coal-fired high-pressure steam, to laundry, kitchen, sterilizers. Low pressure to radiation for the wards. |

| Lighting | Electric, from steam-driven generators. |

| Water supply | Connected to the City of Weyburn. Not reliable in early years. Supply adequate from provincial dam after 1948. Supply insufficient for gardens during the drought of the 1930s. |

| Plumbing | Toilet and bathing fixtures adequate, discharge to City of Weyburn system. |

| Fire History | Hog and horse barns were burned in 1956 and 1965. In 1961, six patients died of smoke inhalation during a fire started in a mattress. |

The Buildings

“The design is so attractive and the building so well-proportioned that it is difficult to realize its size and capacity until one traverses the long corridors and spacious, sunny apartments……..the building is most attractive, sunny and cheerful, while admirably adapted for its purpose as a hospital for the mentally ill.” ~ from Under the Dome, 1986

The contract for phase 1 construction (centre block plus two wings, completed in 1921) was the largest contract let to that date in the province. A construction camp for 250 men was provided for the work. Construction machinery was powered by steam and electricity. After the 1929 addition of the north-west wing, the Weyburn hospital was said to be the biggest building between Winnipeg and Vancouver. It featured double-loaded corridors, numerous airing verandahs, and the great majority of beds were in large dormitory spaces. Corridors were 13′-4″ wide, adequate for exercise and service traffic. Wings were separated from the centre block by fire doors, but the 1921 plans show no fire doors in the 300 ft length of corridors in each wing. That length was not relieved by daylight or window ventilation, due to walls between corridors, day-rooms and dormitories.

Dining rooms in the centre block were large, one for men, one for women. In 1937 each room was furnished with long, white, wooden tables and benches. Capacity was 300 patients per sitting. Service was provided by 10 to 14 patients under one staff supervisor. For Class A service, food was placed in metal bowls before entry of patients. Only spoons were allowed. Class B service was cafeteria style, using china plates, knife, fork, and spoon. Rooms were washed by patients after each meal, walls and floors included. If done quickly, the washers were taken for a walk on the grounds, returning to work after the next meal. Centralized dining was terminated in 1956. It was replaced by small dining rooms on many wards, using tables for 4 and good cutlery. Food was served from heated carts.

The footprint of the Weyburn plan and the basic layout was identical to a design submitted in a competition for a New Bethlem Hospital in London, England, in 1810-11. As a competition entry, there may have been no detailed plan, but the general form and location of offices and galleries were strikingly similar to the Weyburn footprint. To borrow from the past in this way is in line with architectural thinking which often consults past forms and styles in design with little concern for intervening functional changes and technical developments.

Beginning in the 1970s the main hospital building was converted for use by various regional government offices, except for a small portion which remained in use as a psycho-geriatric facility. The former nurse’s residence became a regional psychiatric treatment centre. Possible new office facilities and demolition of the main hospital structure were rumoured in Weyburn when I visited there in 2000. In 2008 the buildings were still in use, and local news articles announced demolition. Removal of hazardous materials and a slow demolition process were started.in the winter of 2008-2009. The main building had disappeared by the summer of 2009. A few relics remain in a display at the Soo Line Museum in Weyburn organized by Ane Robillard, former psychiatric nurse and editor of the hospital history, Under the Dome.

Grounds, Farms, and Gardens

Typical of all western Canadian asylums, farming at Weyburn was of high importance for production and therapy. The farm originally was under control of the Department of Public Works. In 1922 there was no farm manager, and the hospital gardener took charge. Most of the work was done by male patients, including tending of the flower gardens and hospital cemetery grounds. Patient workers were organized in gangs, with 9 to 12 workmen under a gang-man. In the early 1920s, many patients were working at some job, inside or outside the building.

The farm operation was expanded to produce oats, swine, milk, beef cattle, sheep and chickens. 10 workhorses were used in the 1920s, expanding to 21 in 1945. In 1940, 40 sheep and 621 hogs were tended, with 650 acres in cultivation. Some excess produce was sold. A dairy herd was bought from the North Battleford Hospital in 1946. By 1960, four square miles of land (2560 acres) were in use. Pride in high-quality livestock prevailed at Weyburn. Animals were shown and prizes won at local, provincial, and national shows. Visits were occasionally made to neighbouring states across the international border, and a few brood sows were sold to American buyers. Surveys in 1952 challenged the therapeutic value of farm work. It was noted that increased numbers of aging patients were not able to do the hard physical work required. By 1965 1000 acres of land were sold, and the remaining farm and gardens were reorganized for rehabilitation and training of patients, rather than for food production.

In the first two years of operation, 1920and 1921, 20,000 seedlings of maple, cottonwood, and willow were obtained from the grounds of the Legislative Buildings in Regina and planted at the hospital. A greenhouse was built in 1924 and produced up to 30,000 bedding plants per year for hospital grounds and gardens. The circular ornamental garden at the hospital entry was completed in 1925. Flowers were supplied to the hospital wards, offices, and entries. The greenhouse and gardens also supplied provincial courthouses at the nearby communities of Weyburn, Estevan, and Arcola. In the 1930s the river dried up, and gardens were unproductive. A Report of Commissioners of 1930, led by Dr. Hincks, listed 54 defects, among them, regret that the grounds were not well utilized for benefit of patients or staff.

In 1952 a policy of continuous engagement, a “total push” effort, was initiated to keep patients active utilized spaces outside the Weyburn buildings. Outdoor entertainments included curling, skating, sleigh rides, softball, school garden, manual work, sports field, gymnasium, picnic areas, miniature golf, lawn bowling, croquet, horseshoes, and camping trips using rented buses. Walking parties of 60 to 200 patients were undertaken on the grounds, supervised by 10 to 12 attendants. One 1950s hospital curling team included two patients and competed in the MacDonald Briar national championships. Fishing at Nickle Lake (the water reservoir south of Weyburn) was noted for staff and patients.

Weyburn, like other hospitals, allowed patients to tend small private gardens close to the buildings. That practice continued after the 1950s in Weyburn. In Oliver, Riverview, New Westminster and Weyburn reliable patients were permitted to construct shacks in wooded areas behind the buildings, using scraps of wood, metal, paper, and junk to erect private places in the institutional space. One patient at New Westminster kept a few chickens. Dates are not specified, but this practice appears to have followed the open door policies of the 1950s.

Sheila Kelly worked in Weyburn in 1958 and 1959. She also notes that no attention was given to the landscape. I agree, from my own observations of the period. Colorful beds of ornamental flowers were not planted in the late 1950s, and landscaping was limited to maintenance of perennial shrubs in the circular garden at the main entry, and a few trees and shrubs remained along the walls of the building.

Institutional Life

“The patients’ outgoing and incoming mail was censored. The patients who had parole were allowed to go downtown, some had 50 cents to spend. Sunday morning patients were served coffee, otherwise it was tea. Pie was served once a week and fish was served on Friday.” ~ from Under the Dome, 1986

“The patients refer to the airing courts as “bull pens”. For the months of the year when they are in use, the patients walk in aimless fashion round and round the enclosures. There is a mingling of low grade demented types with those who are in better mental condition. Such airing courts have no place in the treatment of mental patients.” ~ C.M. Hincks, 1930

A Report of Commissioners of 1930 was the first to give a full, independent picture of early Weyburn operations. The authors, led by Dr. Hincks, listed 54 defects, among them regret that the grounds were not well utilized for benefit of patients or staff. The report also noted a number of major architectural complaints on planning and design of the building, inadequate fire protection, unheated airing verandahs useless in winter, and regret that the new hospital had floor, walls, and ceilings in poor condition. The four airing-courts, two for female patients and two for male patients, bounded by high board fences and with neither grass nor trees, received much specific criticism.

Weyburn was a catch-all for many kinds of people with nowhere else to go. That difficulty was aggravated by the multi-function operation in Weyburn. Medical, nursing, and administrative staff all noted the difficulty of the multi-function operations of the hospital. Possibly it was planned that way, but the confinement of psychiatric patients (including tubercular cases), and of mentally handicapped, epileptic, and crippled people all under one roof created a difficult and dangerous situation.

In 1922 a School of Defectives was established at Weyburn. It taught cleanliness and housework to older girls, some of whom were placed in charge of dining rooms. Saskatchewan in the 1920s had no other facility for crippled children. In his 1928 annual report, Dr. R.M. Mitchell complained, “We get a larger percentage of crippled children who are not affected mentally. These patients should be in a sick children’s hospital but because of the scarcity of such, they are sent to us.” In 1946, 700 patients in this group were moved to temporary quarters at the Weyburn Airport. In 1948 the new Training School in Moose Jaw received all retarded patients from the airport plus those still in the main hospital. Some nursing staff also made the transfer.

Dr. Hincks was in Saskatchewan in 1944-45, to look at mental health in conjunction with a 1944 general medical study of the province by Dr. Henry Sigerist. In his 1945 report, Hincks complimented Weyburn for the abandonment of airing courts and physical restraint, removal of window bars, but noted that …“unfortunate structural arrangements”…. of the Weyburn hospital made it …..” difficult or impossible to segregate patients according to type in reasonably small groups.” Recommendations for Weyburn included new construction projects, including a new hospital (reduced from 2000 to 1200 bed capacity), a new training school for defectives (1000 beds), a home for the aged and mentally ill (300 beds), a psychiatric division at Saskatoon General Hospital (50 beds), and a nurses residence at Weyburn. Dr. Hincks felt that the design for the new hospital should be based on the cottage concept of one or two storey buildings, as had been constructed at Whitby, Ontario in 1916 because it provided adequate segregation of patients according to the type of illness. Several new service buildings were recommended, and the possibility of alterations to improve the functionality of the Weyburn building was suggested. The building provided basement quarters with continuous flowing baths (subject to water supply) and washable concrete floors for disturbed, incontinent. As late as 1947, Dr. Sam Lawson, newly appointed superintendent, observed that; …..” the whole basement area was a shambles, naked people all over the place, lying around, incontinent. There was a lot of seclusion in use, and mechanical restraints.”

Confinement of people with tuberculosis, the “White Plague”, was difficult at any time and place. Sanitariums were in operation in Saskatchewan after 1917, but under crowded conditions, mental hospitals experienced a ten-fold increase in the disease compared to its public incidence. In 1924 there were 85 active cases in the Weyburn hospital, in a total population of 728. By 1929 Dr. Hincks surveyed Saskatchewan mental hospitals, assisted by Dr. S.R. Laycock, of the University of Saskatchewan, and Dr. O.E. Rothwell, a psychiatrist. They were appalled at the number of tubercular cases in mental hospitals. Subsequent to this survey a dozen verandahs were closed in, vented and heated, and used as wards for tubercular patients. The bed capacity in these areas was increased by 150 beds, but dust infiltration during the black blizzards of drought years caused the tracking of tubercular and other contagious organisms throughout the main building. In 1937 tubercular cases were removed to a special annex and in 1952 tubercular patients in North Battleford were moved to Weyburn, but in spite of improved X-ray equipment, restricted movement of staff and patients to and from the annex, and a large, province-wide budget increase to tackle the problem, it was 1963 before the Weyburn hospital was declared free of tuberculosis.

The issue of overcrowding at Weyburn repeated the experience of North Battleford and other western asylums, where population increase and incidence of mental illness were always a few years ahead of space and staff available. The Weyburn building was designed for 1040 beds in its 3 wings, including 90 single rooms and 30 identical dormitories, assuming that basements were used as sleeping space. There were 18 dayrooms. In crowded years attic space was used for bedrooms for attendants and manageable patients. In the 1920s most staff lived in the main building, occupying hospital bedrooms especially on the children’s ward. In 1937 Dr. C.M. Hincks complained of this fact. He noted that nurses were still occupying bedrooms, thus reducing ward efficiency. Hincks 1945 report repeated critical comments in earlier reports, noting that crowding of the Weyburn hospital had been aggravated by converting basement space for use as wards and day-rooms. In 1946 the population peaked at 2409, excluding patients in the TB Annex. Space for the extra beds would be found by doubling single rooms, or by placing beds in corridors, verandahs (closed and heated), or in the assembly hall in the administration block. Under extreme crowding, day room activities were not possible, sitting in corridors was restricted, and patients used their beds for daytime relaxation.

Although in the 1920s and 1930s custodial care was the main operational concern, “work and water” therapy was in effect. An estimated one half of the patient population was engaged in work of one kind or another, and continuous bathing as hydrotherapy frequently strained the hospital water supply. From 1921 to 1955, housekeeping was done by patients supervised by nurses. This work included the blocking of floors. Patients spent hours pushing cloth bound heavy wooden blocks on long handles over the waxed floors. Repair and maintenance of personal and hospital articles was well organized in Weyburn. In 1923, 1792 pairs of boots were repaired, along with suspenders and mitts. Belts for farm machinery, and mechanical equipment were maintained. In 1944, 8472 wool mattresses, and 2175 canvas “strong mattresses” were repaired. These operations required 4 to 8 patients assisting with the work of shoe-making, mattress repair, and upholstery. Another staff event of note was the cleaning of the marble walls and floors, and the polishing of brass on the “Golden Staircase” of the entry lobby. Polishing was reserved for punishment of nurses and attendants who had misbehaved.

One patient admitted in 1935 reported that some of the patients were assigned to work areas. There were many gangs where each group of patients would be supervised by two staff. There was a snow gang, coal gang (that unloaded boxcars of coal to the Power House), greenhouse gangs, farm gangs, laundry gangs (both in the laundry and transporting laundry to and from the wards). The ice gang hauled ice from the river to the ice house on the farm. Patients also worked in dining rooms, vegetable room and scrubbing floors (eg. Assembly Hall).

Various staff memoirs of the hospital indicate a considerable variety of activities for patients. Indoor activities included annual parties, physical exercises, school work (reading and writing), Christmas program, craft sale, poolroom, shuffleboard, music, hobbies, games room, auditorium games, library, and weekly dances. Movie presentations were held, with nurses in required attendance after their 12 hour work day. A bowling alley was constructed in 1956, in basement space made available after the start of hospital de-population. A staff band was paid for staff dances, but not for patient affairs. Staff memoirs say little about occupational therapy. In 1921, two acres of land were devoted to willow production to supply basket makers in occupational therapy. Formal occupational therapy began in 1923. Prior to the 1956-59 alterations projects, large attics existed over all wings. A staff poolroom was in use in one attic.

Psychiatric nurse Sheila Kelly worked in Weyburn in 1958 and 1959. She was engaged in the work of assessment of arrivals and was not occupied on the chronic wards. I was there at that time, working on the renovations project, but it was a big place and we did not meet. Sheila notes that after her work in the Oliver hospital in 1955 and 1956, she was pleased to find the, ”pleasantly painted walls, bright drapes, and comfortable furniture,” of the Weyburn building.

Sources

C.M. Hincks and S.R. Laycock. Report of Commissioner re; Provincial Mental Hospitals and Mental Hygiene Conditions in of the Province of Saskatchewan. Regina: Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly, 7th Leg. 2nd Sess. Sessional Papers No. 27, 1930.

F.H. Kahan. Brains and Bricks. Regina: White Cross Publications, 1965.

No author. “A Mental Health Program for Saskatchewan,”A Report Submitted by The National Committee to the Government of the Province of Saskatchewan. Regina: King’s Printer, 1945.

Helen Rosenau. Social Purpose in Architecture. London: Studio Vista, 1970.

Under the Dome: The Life and Times of Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, Ane Robillard, ed. Weyburn, Saskatchewan: Souris Valley History Book Committee, 1986.