Weyburn

Name(s) of Institution:

Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn

Saskatchewan Mental Hospital, Weyburn (1921)

Souris Valley Extended Care Hospital (renamed 1971)

Opened:

1921 – approved for demolition in 2006 and demolished in 2009

Location:

Weyburn, Saskatchewan

Period of De-institutionalization:

1955-1971

Patient Demographic:

The hospital had separate male and female wards, with a designated ward for people diagnosed with mental disabilities. At its peak in the mid-1940s, the hospital had a patient population of 2,500.

According to a 1945 mental hygiene survey of the province’s mental hospitals (preceding Saskatchewan’s deinstitutionalization era), Weyburn’s patient population was 1,445 over capacity. For example, on January 7, 1963, the population was 1,492; by December 28, 1970, it stood at 360.

De-institutionalization:

As early as the 1950s, Saskatchewan’s Psychiatric Services Branch (PSB) considered closing Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, along with its counterpart in North Battleford. The downsizing of the patient population at Weyburn, which began in the late 1950s, was a direct result of two programs: the provincial “Saskatchewan Plan,” and an institutional initiative specific to Weyburn and directed by Hugh Lafave.

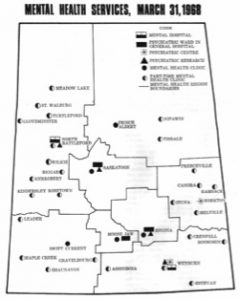

Under the Saskatchewan Plan, introduced by the PSB in 1955, the province was divided into eight regions. Instead of relying primarily on the two provincial mental hospitals, regions were tasked with establishing community-based mental health centres and support systems, including psychiatric wards in general hospitals, psychiatric centres, mental health clinics (in-patient centres), and part-time mental health clinics (outpatient centres).

While the Saskatchewan Plan quickly became the guiding design for the future of Saskatchewan’s psychiatric services, it was not embraced until the election of a provincial Liberal government in 1964, and even then it was only partially implemented. The new government adopted an aggressive policy of deinstitutionalization with cost reduction as a guiding principle. In addition, the hospital developed a program that relied on alternatives to long-term residential care, such as developing new treatments for the patients and establishing links to community-based mental health programs. From 1963 to 1970, under these two agendas, the patient population at the hospital plummeted markedly.

In 1971, the government closed Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn. The building remained, however, and officials decided to convert part of it into the Souris Valley Extended Care Hospital (a nursing home) with an eighty-four-bed psychiatric centre. This was an attempt to lessen the economic impact of institutional closure on the community of Weyburn. In 2006, the government closed the hospital, and in 2009 it was demolished.

Trans-institutionalization:

The 1955 Saskatchewan Plan called for the closure of the province’s two large mental hospitals and the development of a network of eight regional systems of community-based services and links to general hospitals with psychiatric wings (North Battleford, Prince Albert, Weyburn, Yorkton, Moose Jaw, Regina, Saskatoon, and Swift Current). Regional clinics could offer in-patient services, but the goal of the PSB was to develop local, community-based mental health services that provided treatment and support closer to patients’ family and friends.

Between 1960 and 1963, the University Hospital in Saskatoon conducted a study that demonstrated many long-stay psychiatric patients could be successfully helped, managed, and treated in a general hospital psychiatric ward and then released into the community.

From 1963 to 1971, the Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, adopted a new program that provided alternatives to care in a mental hospital. Under this initiative, staff developed rigorous programs for the chronically ill and began to rely more on regional treatment centres, resulting in a marked decline in patient populations in the two long-stay provincial facilties.

When the Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, closed in 1971, some patients remained as residents of the Souris Valley Extended Care Hospital’s eighty-four-bed psychiatric centre. Many other patients were transferred back to their home regions by the PSB and were placed in group homes, nursing homes, and geriatric centres. Others the PSB placed in “approved homes” where unskilled and untrained guardians watched and cared for them. The Canadian Mental Health Association argued that these were merely custodial institutions where the quality of life was lower than it had been in the large mental institutions.

Work Therapy into Occupational Therapy:

Since its opening in 1921, the hospital at Weyburn had its patients clean the wards, sew clothing, and tend to the hospital’s farms, gardens, and livestock—all in the name of work therapy. The administration used these activities ostensibly to provide the patients with therapy while at the same time keeping them from remaining idle. While the practice may have started with that ideal in mind, in reality, work therapy soon became a way to keep hospital costs down at the expense of patient labour.

Both provincial hospitals ended the practice of patient labour in the early 1950s, influenced by the increasing expense of industrial farming in a post-war era by the growing perception that it was inhumane to have patients do such work, and by the shifting place of the institution in mental health services. While the provincial government sold what it could of the hospital farmland, Weyburn continued to offer simpler well-established “occupational therapies” such as sewing and woodworking. Increasingly, however, hobby-oriented activities that aimed to help patients pass the dreary hospital days were seen as dated and not helpful to patients in need of a trade or occupation once they were released from the hospital into the community.

As a supplemental service, the staff at Weyburn developed a recreation program. This grew out of a similar service that the staff had established for themselves. What began as a small physiotherapy unit designed to help patients recover from physical ailments blossomed into an award-winning recreation program. All patients were permitted to participate in this recreation therapy, which included gymnastics, staff–patient sports teams, and an annual patient sports day.

In 1957, the same year the PSB announced it was implementing a plan to close the hospital, the American Psychiatric Association presented the Saskatchewan Mental Hospital, Weyburn, with the Award of Merit for its care of people with mental illnesses.

Patient into Person:

By 1954, a “patient council” at Weyburn, supported by the hospital administration, organized many of the patient activities.

Before the 1950s, during the hospital’s work therapy days, the staff gathered the patients together to participate in the offered therapies. They did this out of their own convenience and not necessarily for the individual benefit of the patients. In the mid- to late-1950s, as Weyburn shifted focus from patient work to recreation, the staff began formulating therapies aimed at serving the individual needs of the person under care.

Staffing in the De-institutionalization Era:

In 1948, Saskatchewan developed a two-year psychiatric nursing program. The first graduates of this new mental health education initiative graduated two years later, signalling the arrival of standardized qualification in provincial mental health facilities. By the 1960–61 academic year, the province had introduced a block system of instruction that established a three-year course: two years of instruction and one year of training. This was to keep Saskatchewan’s mental health nursing program on par with general nursing schools across the nation.

With Weyburn set to close and Saskatchewan on the path of deinstitutionalization, psychiatric nurses at the Weyburn mental hospital expressed professional concerns. The Liberal government under Ross Thatcher decided to employ these nurses in community-based programs, providing follow-up services to former patients. Still, de-institutionalization meant the loss of the city’s largest employer—a difficult situation. In the drama of closing the local facility, the provincial government both cut and froze wages, resulting in a personnel crisis and a decline in the quality of care within the rapidly shrinking hospital.

Sources:

Dickinson, H. D. The Two Psychiatries: The Transformation of Psychiatric Work in Saskatchewan, 1905–1984. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1989.

Dooley, C. “The End of the Asylum (Town): Community Responses to the Depopulation and Closure of the Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn.” Historie Sociale/Social History 44, no. 88 (2011): 331–354.

Dyck, E. “Spaced-Out in Saskatchewan: Modernism, Anti-Psychiatry, and Deinstitutionalization, 1950–1968.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 84, no. 4 (2010): 640–666.

Hincks, C. M. Mental Hygiene Survey of Saskatchewan. Regina: Thomas A. McConnica, King’s Printer, 1945.

Marchildon, G. “A House Divided: Deinstitutionalization, Medicare and the Canadian Mental Health Association in Saskatchewan, 1944–1964.” Histoire Sociale/Social History 44, no.88 (2011): 305–330.

Province of Saskatchewan. Annual Report of the Department of Public Health. Regina: Department of Public Health, 1967–1968.

Richert, L., and B. Wickham. “Sports and Recreation as Medicinal: Saskatchewan Hospital, Weyburn, in the 1950s.” Saskatchewan History 65, no. 1 (2013): 12–17.