The Brandon Asylum, 1891

Location

Brandon, Manitoba

Current Name

Brandon Mental Health Centre

The Site

The Brandon Asylum served the western farmlands of Manitoba and accepted the majority of cases from the North West Territory. Situated on farmland above the gently sloping banks of the Assiniboine River, it features views of the valley to the south, to farmland beyond, and was originally open prairie on all sides.

The City of Brandon continues to approach from the west. Housing developments are now close on the west side of the hospital, and may eventually surround the facility. Farm holdings supplied the hospital for many years and made the property an attractive development prospect prior to its conversion to a community college. In spite of the sloping land, the site of the 1891 building was not well graded. Flooded basements were common, and a shallow vegetable root house had been ventilated by air coming from adjacent stables.

Architectural and Service Details, 1891 and 1912 buildings.

| Architect | Samuel Hooper, Provincial Architect |

| Floor Area | 1912 bldg. Approximately 172,000 sq.ft including basement |

| Height | 4 stories including basement |

| Constructions Costs | $30,000 (1891 building), $454,878 (1912 building) |

| Description | Monolithic, axial symmetry, “E” Plan (1912 Building) |

| Occupancy | 1000 (1912 Building), reports vary |

| Structural | 189 building similar to Selkirk but interior construction inferior. Masonry exterior bearing walls, wood frame interior walls, floors and roof. Wood floors water damaged by leaking pipes. 1912 building steel frame, concrete floors. |

| Heating | Coal-fired hot water in 1891, inadequate using inefficient old equipment located within the main building. Replaced with steam boilers in 1904 provided power for generators. |

| Lighting | Electric, steam-driven generators. |

| Water Supply | An ample supply of water was found, supplied by a well 275 feet deep. |

| Plumping | Sewage was piped to the Assiniboine River a few miles to the East. |

| Fire History | None noted in hospital history or by Hurd. |

The Buildings

“The division walls on the wards are of ordinary studding and lath and plaster, with narrow baseboards, while the floors are not watertight, so that any nuisances committed affect the ceilings below; the plumbing throughout is bad and the water closets defective; the fire protection and water supply, as well as the heating, are also quite inadequate.” Henry M. Hurd., 1917.

“It was built to house 1000 patients, and supposed to be the last word in suitable accommodation for the “insane”. It was anything but suitable, and by 1919 was obsolete.” Henry M. Hurd., 1917.

The large building completed in Brandon in 1890 by the province of Manitoba was intended as a reform school for boys. After a year of negotiations, the Provincial and Dominion governments agreed to convert it for use as an asylum for the insane. It opened in 1891 to shelter patients from Manitoba and the North West Territories. Henry Hurd, in 1917, stated that the 1891 Brandon design was similar to that of Selkirk, but of low-quality construction. The original building was enlarged in 1893 in order to accommodate psychiatric cases from the Stoney Mountain Penitentiary, and again in 1903 in response to overcrowding due to patients coming from the North West Territory. The absence of airing verandahs on the plans did not satisfy sound hospital practice on the need for fresh air at all seasons. Not sure where this comes from or which building because Arthur notes that there were no surviving plans for the first building – but this is an important point. The entire structure was destroyed by fire in 1910. Patients were sheltered for two years in Brandon’s Winter Fair Building pending completion of a new hospital in 1912.

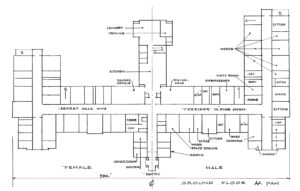

Plans of the 1891 hospital and its 1903 addition have not been found. The 1891 building was not suitable as an asylum. According to hospital inspections it was troubled with settling floors and roofs. The 1912 hospital, like the Selkirk asylum, had single rooms and small ward accommodation. The ground floor plan does not show any dormitory or large day-room spaces. Six small sitting rooms are shown on the ground floor plan. Corridors were 11′-6″ wide, adequate for walking exercise and service traffic.

The 1912 asylum, now identified as the Parkland Building, is a large, imposing structure. It exhibits what is possibly the most imaginative exterior design of early Western Canadian mental hospitals. It follows no particular style, but its eclectic mix of details and unusual cupola, entry wall and ornamentation reflect a level of enthusiasm in design unusual in the Western Canadian buildings. The new building was fire resistant with up to date mechanical and electrical services and a separate boiler plant.

Hincks’ 1918 CNCMH survey recommended rearrangement of the Brandon building to provide additional wards, separate reception ward, recreation rooms, sunrooms, laboratory facilities, and a separate building for dining service. Occupational buildings, adequate staff quarters, and special accommodation for tubercular patients were also urged. In his 1921 follow up to the 1918 survey, Hincks was pleased to note great improvement in mental health funding in Manitoba. He wrote, “Manitoba is conducting a great humanitarian and health experiment, and results will be watched with the keenest interest. In all, 2.3 million dollars had been spent in 3 years for mental health services.” 1.4 million of that sum had been allocated to the Brandon facility; $ 750,000 for an acute care building, $500,000 for a nurse’s residence, a building for chronic cases, and construction of laboratories, library, and staff quarters. Later buildings at the Brandon site are also well conceived and executed, generally in warm brick colours, with delicate brick patterns at the 1932 Women’s Pavilion and attractive al fresco plasterwork in the dining room of the Nurses Residence.

In 1979 Smith Carter, Architects, of Winnipeg, undertook a study of the entire Brandon facility to report on improvement of buildings. Fire safety improvements, mechanical and electrical services, and site development were key issues. The report recommended a new complex of buildings to replace the existing structures. Implementation of the report was cancelled by Manitoba’s move to community care and de-institutionalization. The downsizing of the hospital population begun in the 1950s and open wards were in use in 1957. Some were reluctant to leave after decades in hospital.

The Brandon Mental Health Centre was closed in 1998, but the buildings were in excellent condition when I visited them in 2000. At that time they were waiting for resolution of a vigorous public debate about preservation and/or adaptive re-use of the buildings and the site. In 2009 a new secondary education development was announced for the property.

Grounds, Farms and Gardens

Patient labour was used far more extensively than just in the farm and garden. Draying coal was one example, but there were many other areas in which the patients did the bulk of the work. In 1902 two miles of fence was built, and about a half a mile of road graded, and the same of ditching done.

The frontal area of the grounds is gently sloping land, facing south with views to the valley of the Assiniboine River. The layout of landscaping in that area in 2000 was informal, with a non-symmetrical plan of driveways, lawns, walks and planting areas. A broad, terraced promenade, with outdoor seating, leading to the main entry from parking areas. Trees were of considerable age and appeared to be in good health. Drawings of early site plans and of changes to the grounds have not been found. Planting of the frontal southern areas of the hospital grounds took decades to produce a mature growth of sheltering trees and hedges.

The well-treed areas of the grounds were available for walking recreation, and for resting on benches along the walks. Manageable patients walked twice daily in groups escorted by hospital staff. Recovering patients could be given passes to visit the grounds without supervision. The majority of patients were exercised in airing yards at the rear of the building. Photographs of the facility reveal that the pleasant landscapes of the frontal areas were not consistent with the fenced, unshaded, and windswept patient airing yards at the rear of the buildings. Smaller “bull pens” of uncertain design and date were for exercise of disturbed patients. By 1905 there were two 5-acre recreation yards (male and female), with wooden fences eight ft high. They were regularly used by staff, with a few capable patients joining games of baseball, cricket, and football. In 1892 outdoor curling and skating were planned on flooded and frozen portions of the yards. Some undated exterior improvements were made in the 1920s and 1930s. The pens were torn down, and high board fences around large parks were planned for replacement with hedges and maple trees. In spite of repeated objections by hospital inspectors, the airing yards remained in use until 1959.

Following construction of the 1903 addition to the original 1891building, extensive landscaping was started in 1904. It included planting of various kinds, with cherry trees throughout the grounds. Hedge rows were planted for privacy and wind breaks, and wild roses were distributed in beds and rows. A greenhouse, 11 ft X 70 ft, supplied flowers to the wards in the hospital. An ornamental garden at the Old Colony Building, including fish ponds, was built by patient labour and named Stanley Park.

The orchard in time produced plums, crab-apples, raspberries, currants, gooseberries, and sand cherries. In 1926 a provincial tree nursery was started. It was maintained by patients supervised by garden staff and produced seedlings for planting at Manitoba public schools. In 1927 an experimental crop of tobacco produced a good yield.

Burgess, in 1898, reported that farming was the main activity at Brandon. Refvik notes the therapeutic intent of that work. Farming operations at Brandon were highly successful. In addition to its own land, the hospital rented two farms and produced a variety of vegetables, meat, milk, eggs, and other products. In 1905 the hospital accounts showed a significant benefit of $17,500.00 attributed to patients’ work on the farm and gardens, and in construction activity.

Patient Life

Reports of patient population at Brandon indicate heavy use of the institution in the early decades, followed by a drop in patient numbers following the construction of institutions in other prairie provinces. In 1892, only one year after its doors had opened, superintendent Dr. McFadden noted severe crowding and urged more single rooms at the new institution. In 1896 the Brandon Mail suggested that the attics and basements of both Manitoba asylums might have to be occupied by beds, due to the high rate of new applications. Hurd recorded that in 1908 the hospital was crowded. It had a rated capacity of 420 beds, with an actual population of 557 patients. Beds were placed on stair landings, some were on floors of day-sitting rooms, and the assembly room was filled. Subsequent use of attics and basements added 20% to bed capacity, confirmed in the annual report of the hospital in 1910. At the worst of crowded conditions, some patients were obliged to sleep in closets and storerooms on wooden shelves. It was said that beds were so close that patients could not fall out. Corridors were occupied at night with straw mattresses, 8 trunk rooms were filled with 20 beds each, and each room was lighted and ventilated by one window.

However, in 1917, according to Hurd, the Brandon and Selkirk hospitals had accommodation for 1500 patients and an actual count of 841, in his words, ” an unusual fact for asylums.” That tally followed the transfer of patients to Saskatchewan and Alberta hospitals. With this exception, all commentators indicated that accommodation consistently failed to keep up with demand.

Over the objections of the farm supervisor, a 10-acre plot was removed from the farmlands and converted to playing fields. Patients’ sports days were few and far between. After 1905 there was cooperation in community use of playing fields at the hospital, including a measure of patient/community competition. At Thanksgiving in 1905, patients played the Brandon College team. By 1925 a small golf course was in operation on the grounds. Soccer was widely played in Western Canada before World War Two. The “Brandon Mental Football Club” composed of staff members, was active from 1929 to 1934, in the community and provincial matches.

According to Refvik, in 1891 the Brandon Asylum activities program read like an advertisement for moral management in psychiatry. Ten tickets to the Brandon Fair were donated for use by patients and attendants, and concerts by local entertainers were given at the hospital. Events were cancelled in 1892 due to crowding but continued in the 1890s. They included attendance at the racetrack for trusted patients, sleigh and carriage rides in season, curling (using sets of donated rocks), Christmas and Thanksgiving festivals, lantern slide shows, and bi-weekly dances for patients in the winter season. A movie projector arrived in 1921. Refvik is cautious about these statements, noting possible exaggeration by the Brandon press reporting on the hospital.

Sources

T.J.W. Burgess. Presidential Address to the Royal Society of Canada, Transactions, Section IV, Geological and Biological Sciences, 1898.

C.M. Hincks. “Survey of the Province of Manitoba,” Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene, vol.1, 1919-1920.

Henry M. Hurd. The Institutional Care of the Insane in the United States and Canada. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1917.

T.A. Pincock. “A Half Century of Psychiatry in Manitoba,” in Canada’s Mental Health. Ottawa: Department of National Health and Welfare, 1970.

Kurt Refvik. History of the Brandon Mental Health Centre. Brandon: Brandon Mental Health Centre, 1991.